What happens when the tools and technologies we use every day become mainstream parts of the business world? What happens when we stop leading separate “consumer” and “professional” lives when it comes to technology stacks? The result is a dramatic change in the products we use at work and as a result an upending of the canon of management practices that define how work is done.

What happens when the tools and technologies we use every day become mainstream parts of the business world? What happens when we stop leading separate “consumer” and “professional” lives when it comes to technology stacks? The result is a dramatic change in the products we use at work and as a result an upending of the canon of management practices that define how work is done.

This paper says business must embrace the consumer world and see it not as different, less functional, or less enterprise-worthy, but as the new path forward for how people will use technology platforms, how businesses will organize and execute work, and how the roles of software and hardware will evolve in business. Our industry speaks volumes of the consumerization of IT, but maybe that is not going far enough given the incredible pace of innovation and depth of usage of the consumer software world. New tools are appearing that radically alter the traditional definitions of productivity and work. Businesses failing to embrace these changes will find their employees simply working around IT at levels we have not seen even during the earliest days of the PC. Too many enterprises are either flat-out resisting these shifts or hoping for a “transition”—disruption is taking place, not only to every business, but within every business.

Paradigm shift

Continuous productivity is an era that fosters a seamless integration between consumer and business platforms. Today, tools and platforms used broadly for our non-work activities are often used for work, but under the radar. The cloud-powered smartphone and tablet, as productivity tools, are transforming the world around us along with the implied changes in how we work to be mobile and more social. We are in a new era, a paradigm shift, where there is evolutionary discontinuity, a step-function break from the past. This constantly connected, social and mobile generational shift is ushering a time period on par with the industrial production or the information society of the 20th century. Together our industry is shaping a new way to learn, work, and live with the power of software and mobile computing—an era of continuous productivity.

Continuous productivity manifests itself as an environment where the evolving tools and culture make it possible to innovate more and faster than ever, with significantly improved execution. Continuous productivity shifts our efforts from the start/stop world of episodic work and work products to one that builds on the technologies that start to answer what happens when:

- A generation of new employees has access to the collective knowledge of an entire profession and experts are easy to find and connect with.

- Collaboration takes place across organization and company boundaries with everyone connected by a social fiber that rises above the boundaries of institutions.

- Data, knowledge, analysis, and opinion are equally available to every member of a team in formats that are digital, sharable, and structured.

- People have the ability to time slice, context switch, and proactively deal with situations as they arise, shifting from a world of start/stop productivity and decision-making to one that is continuous.

Today our tools force us to hurry up and wait, then react at all hours to that email or notification of available data. Continuous productivity provides us a chance at a more balanced view of time management because we operate in a rhythm with tools to support that rhythm. Rather than feeling like you’re on call all the time waiting for progress or waiting on some person or event, you can simply be more effective as an individual, team, and organization because there are new tools and platforms that enable a new level of sanity.

Some might say this is predicting the present and that the world has already made this shift. In reality, the vast majority of organizations are facing challenges or even struggling right now with how the changes in the technology landscape will impact their efforts. What is going on is nothing short of a broad disruption—even winning organizations face an innovator’s dilemma in how to develop new products and services, organize their efforts, and communicate with customers, partners, and even within their own organizations. This disruption is driven by technology, and is not just about the products a company makes or services offered, but also about the very nature of companies.

Today’s socialplace

The starting point for this revolution in the workplace is the socialplace we all experience each and every day.

We carry out our non-work (digital) lives on our mobile devices. We use global services like Facebook, Twitter, Gmail, and others to communicate. In many places in the world, local services such as Weibo, MixIt, mail.ru, and dozens of others are used routinely by well over a billion people collectively. Entertainment services from YouTube, Netflix to Spotify to Pandora and more dominate non-TV entertainment and dominate the Internet itself. Relatively new services such as Pinterest or Instagram enter the scene and are used deeply by tens of millions in relatively short times.

While almost all of these services are available on traditional laptop and desktop PCs, the incredible growth in usage from smartphones and tablets has come to represent not just the leading edge of the scenario, but the expected norm. Product design is done for these experiences first, if not exclusively. Most would say that designing for a modern OS first or exclusively is the expected way to start on a new software experience. The browser experience (on a small screen or desktop device) is the backup to a richer, more integrated, more fluid app experience.

In short, the socialplace we are all familiar with is part of the fabric of life in much of the world and only growing in importance. The generation growing up today will of course only know this world and what follows. Around the world, the economies undergoing their first information revolutions will do so with these technologies as the baseline.

Historic workplace

Briefly, it is worth reflecting on and broadly characterizing some of the history of the workplace to help to place the dramatic changes into historic context.

Mechanized productivity

The industrial revolution that defined the first half of the 20th century marked the start of modern business, typified by high-volume, large-scale organizations. Mechanization created a culture of business derived from the capabilities and needs of the time. The essence of mechanization was the factory which focused on ever-improving and repeatable output. Factories were owned by those infusing capital into the system and the culture of owner, management, and labor grew out of this reality. Management itself was very much about hierarchy. There was a clear separation between labor and management primarily focused on owners/ownership.

The information available to management was limited. Supply chains and even assembly lines themselves were operated with little telemetry or understanding of the flow of raw materials through to sales of products. Even great companies ultimately fell because they lacked the ability to gather insights across this full spectrum of work.

Knowledge productivity

The problems created by the success of mechanized production were met with a solution—the introduction of the computer and the start of the information revolution. The mid-20th century would kick off a revolution in business, business marked by global and connected organizations. Knowledge created a new culture of business derived from the information gathering and analysis capabilities of first the mainframe and then the PC.

The essence of knowledge was the people-centric office which focused on ever-improving analysis and decision-making to allocate capital, develop products and services, and coordinate the work across the globe. The modern organization model of a board of directors, executives, middle management, and employees grew out of these new capabilities. Management of these knowledge-centric organizations happened through an ever-increasing network of middle-managers. The definition of work changed and most employees were not directly involved in making things, but in analyzing, coordinating, or servicing the products and services a company delivered.

The information available to management grew exponentially. Middle-management grew to spend their time researching, tabulating, reporting, and reconciling the information sources available. Information spanned from quantitative to qualitative and the successful leaders were expert or well versed in not just navigating or validating information, but in using it to effectively influence the organization as a whole. Knowledge is power in this environment. Management took over the role of resource allocation from owners and focused on decision-making as the primary effort, using knowledge and the skills of middle management to inform those choices.

A symbol of knowledge productivity might be the meeting. Meetings came to dominate the culture of organizations: meetings to decide what to meet about, meetings to confirm that people were on the same page, meetings to follow-up from other meetings, and so on. Management became very good at justifying meetings, the work that went into preparing, having, and following up from meetings. Power derived from holding meetings, creating follow-up items and more. The work products of meetings—the pre-reading memos, the presentations, the supporting analytics began to take on epic proportions. Staff organizations developed that shadowed the whole process.

The essence of these meetings was to execute on a strategy—a multi-year commitment to create value, defend against competition, and to execute. Much of the headquarters mindset of this era was devoted to strategic analysis and planning.

The very best companies became differentiated by their use of information technologies in now legendary ways such as to manage supply chain or deliver services to customers. Companies like Wal-Mart pioneered the use of technology to bring lower prices and better inventory management. Companies like the old MCI developed whole new products based entirely on the ability to write software to provide new ways of offering existing services.

Even with the broad availability of knowledge and information, companies still became trapped in the old ways of doing things, unable to adapt and change. The role of disruption as a function not just of technology development but as management decision-making showed the intricate relationship between the two. With this era of information technology came the notion of companies too big and too slow to react to changes in the marketplace even with information right there in front of collective eyes.

The impact of software, as we finished the first decade of the 21st century, is more profound than even the most optimistic software people would have predicted. As the entrepreneur and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen wrote two years ago, “software is eating the world”. Software is no longer just about the internal workings of business or a way to analyze information and execute more efficiently, but has come to define what products a business develops, offers, and serves. Software is now the product, from cars to planes to entertainment to banking and more. Every product not only has a major software component but it is also viewed and evaluated through the role of software. Software is ultimately the product, or at least a substantial part of differentiation, for every product and service.

Today’s workplace: Continuous Productivity

Today’s workplace is as different as the office was from the factory.

Today’s organizations are either themselves mobile or serving customers that are mobile, or likely both. Mobility is everywhere we look—from apps for consumers to sales people in stores and the cash registers to plane tickets. With mobility comes an unprecedented degree of freedom and flexibility—freedom from locality, limited information, and the desktop computer.

The knowledge-based organization spent much energy on connecting the dots between qualitative sampling and data sourced on what could be measured. Much went into trying get more sources of data and to seek the exact right answer to important management decisions. Today’s workplace has access to more data than ever before, but along with that came understanding that just because it came from a computer it isn’t right. Data is telemetry based on usage from all aspects of the system and goes beyond sampling and surveys. The use of data today substitutes algorithms seeking exact answers with heuristics informed by data guessing the best answer using a moment’s worth of statistical data. Today’s answers change over time as more usage generates more data. We no longer spend countless hours debating causality because what is happening is right there before our eyes.

We see this all the time in the promotion of goods on commerce sites, the use of keyword search and SEO, even the way that search itself corrects spellings or maps use a vast array of data to narrow a potentially very large set of results from queries. Technologies like speech or vision have gone from trying to compute the exact answer to using real-time data to provide contextually relevant and even more accurate guesses.

The availability of these information sources is moving from a hierarchical access model of the past to a much more collaborative and sharing-first approach. Every member of an organization should have access to the raw “feeds” that could be material to their role. Teams become the focus of collaborative work, empowered by the data to inform their decisions. We see the increasing use of “crowds” and product usage telemetry able to guide improved service and products, based not on qualitative sampling plus “judgment” but on what amounts to a census of real-world usage.

Information technology is at the heart of all of these changes, just as it was in the knowledge era. The technologies are vastly different. The mainframe was about centralized information and control. The PC era empowered people to first take mainframe data and make better use of it and later to create new, but inherently local or workgroup specific information sources. Today’s cloud-based services serve entire organizations easily and can also span the globe, organizations, and devices. This is such a fundamental shift in the availability of information that it changes everything in how information is collected, shared, and put to use. It changes everything about the tools used to create, analyze, synthesize, and share information.

Management using yesterday’s techniques can’t seem keep up with this world. People are overwhelmed by the power of their customers with all this information (such as when social networks create a backlash about an important decision, or we visit a car dealer armed with local pricing information). Within organizations, managers are constantly trying to stay ahead of the curve. The “young” employees seem to know more about what is going on because of Twitter and Facebook or just being constantly connected. Even information about the company is no longer the sole domain of management as the press are able to uncover or at least speculate about the workings of a company while employees see this speculation long before management is communicating with employees. Where people used to sit in important meetings and listen to important people guess about information, people now get real data from real sources in real-time while the meeting is taking place or even before.

This symbol of the knowledge era, the meeting, is under pressure because of the inefficiency of a meeting when compared to learning and communicating via the technology tools of today. Why wait for a meeting when everyone has the information required to move forward available on their smartphones? Why put all that work into preparing a perfect pitch for a meeting when the data is changing and is a guess anyway, likely to be further informed as the work progresses? Why slow down when competitors are speeding up?

There’s a new role for management that builds on this new level of information and employees skilled in using it. Much like those who grew up with PC “natively” were quick to assume their usage in the workplace (some might remember the novelty of when managers first began to answer their own email), those who grow up with the socialplace are using it to do work, much to the chagrin of management.

Management must assume a new type of leadership that is focused on framing the outcome, the characteristics of decisions, and the culture of the organization and much less about specific decision-making or reviewing work. The role of workplace technology has evolved significantly from theory to practice as a result of these tools. The following table contrasts the way we work between the historic norms and continuous productivity.

| Then |

Now, Continuous Productivity |

| Process |

Exploration |

| Hierarchy, top down or middle out |

Network, bottom up |

| Internal committees |

Internal and external teams, crowds |

| Strategy-centric |

Execution-centric |

| Presenting packaged and produced ideas, documents |

Sharing ideas and perspectives continuously, service |

| Data based on snapshots at intervals, viewed statically |

Data always real-time, viewed dynamically |

| Process-centric |

Rhythm-centric |

| Exact answers |

Approximation and iteration |

| More users |

More usage |

Today’s workplace technology, theory

Modern IT departments, fresh off the wave of PC standardization and broad homogenization of the IT infrastructure developed the tools and techniques to maintain, ne contain, the overall IT infrastructure.

A significant part of the effort involved managing the devices that access the network, primarily the PC. Management efforts ran the gamut from logon scripts, drive scanning, anti-virus software, standard (or only) software load, imaging, two-factor authentication and more. Motivating this has been the longstanding reliability and security problems of the connected laptop—the architecture’s openness so responsible for the rise of the device also created this fragility. We can see this expressed in two symbols of the challenges faced by IT: the corporate firewall and collaboration. Both of these technologies offer good theories but somewhat backfire in practice in today’s context.

With the rise of the Internet, the corporate firewall occupied a significant amount of IT effort. It also came to symbolize the barrier between employees and information resources. At some extremes, companies would routinely block known “time wasters” such as social networks and free email. Then over time as the popularity of some services grew, the firewall would be selectively opened up for business purposes. YouTube and other streaming services are examples of consumer services that transitioned to an approved part of enterprise infrastructure given the value of information available. While many companies might view Twitter as a time-wasting service, the PR departments routinely use it to track news and customer service might use it to understand problems with products so it too becomes an expected part of infrastructure. These “cracks” in the notion of enterprise v. consumer software started to appear.

Traditionally the meeting came to symbolize collaboration. The business meeting which occupied so much of the knowledge era has taken on new proportions with the spread of today’s technologies. Businesses have gone to great lengths to automate meetings and enhance them with services. In theory this works well and enables remote work and virtual teams across locations to collaborate. In practical use, for many users the implementation was burdensome and did not support the wide variety of devices or cross-organization scenarios required. The merger of meetings with the traditional tools of meetings (slides, analysis, memos) was also cumbersome as sharing these across the spectrum of devices and tools was also awkward. We are all familiar with the first 10 minutes of every meeting now turning into a technology timesink where people get connected in a variety of ways and then sync up with the “old tools” of meetings while they use new tools in the background.

Today’s workspace technology, practice

In practice, the ideal view that IT worked to achieve has been rapidly circumvented by the low-friction, high availability of a wide variety of faster-to-use, easier-to-use, more flexible, and very low-cost tools that address problems in need of solutions. Even though this is somewhat of a repeat of the introduction of PCs in the early 1990’s, this time around securing or locking down the usage of these services is far more challenging than preventing network access and isolating a device. The Internet works to make this so, by definition.

Today’s organizations face an onslaught of personally acquired tablets and smartphones that are becoming, or already are, the preferred device for accessing information and communication tools. As anyone who uses a smartphone knows, accessing your inbox from your phone quickly becomes the preferred way to deal with the bulk of email. How often do people use their phones to quickly check mail even while in front of their PC (even if the PC is not in standby or powered off)? How much faster is it to triage email on a phone than it is on your PC?

These personal devices are seen in airports, hotels, and business centers around the world. The long battery life, fast startup time, maintenance-free (relatively), and of course the wide selection of new apps for a wide array of services make these very attractive.

There is an ongoing debate about “productivity” on tablets. In nearly all ways this debate was never a debate, but just a matter of time. While many look at existing scenarios to be replicated on a tablet as a measure of success of tablets at achieving “professional productivity”, another measure is how many professionals use their tablets for their jobs and leave their laptops at home or work. By that measure, most are quick to admit that tablets (and smartphones) are a smashing success. The idea that tablets are used only for web browsing and light email seems as quaint as claiming PCs cannot do the work of mainframes—a common refrain in the 1980s. In practice, far too many laptops have become literally desktops or hometops.

While the use of tools such as AutoCAD, Creative Suite, or enterprise line of business tools will be required and require PCs for many years to come, the definition of professional productivity will come to include all the tasks that can be accomplished on smartphones and tablets. The nature of work is changing and so the reality of the tools in use are changing as well.

Perhaps the most pervasive services for work use are cloud-based storage products such as DropBox, Hightail (YouSendIt), or Box. These products are acquired easily by consumers, have straightforward browser-based interfaces and apps on all devices, and most importantly solve real problems required by modern information sharing. The basic scenario of sharing large files with a customers or partners (or even fellow employees) across heterogeneous devices and networks is easily addressed by these tools. As a result, expensive and elaborate (or often much richer) enterprise infrastructure goes unused for this most basic of business needs—sharing files. Even the ubiquitous USB memory stick is used to get around the limitations of enterprise storage products, much to the chagrin of IT departments.

Tools beyond those approved for communication are routinely used by employees on their personal devices (except of course in regulated industries). Tools such as WhatsApp or WeChat have hundreds of millions of users. A quick look at Facebook or Twitter show that for many of those actively engaged the sharing of work information, especially news about products and companies, is a very real effort that goes beyond “the eggs I had for breakfast” as social networks have sometimes been characterized. LinkedIn has become the goto place for sales people learning about customers and partners and recruiters seeking to hire (or headhunt) and is increasingly becoming a primary source of editorial content about work and the workplace. Leading strategists are routinely read by hundreds of thousands of people on LinkedIn and their views shared among the networks employees maintain of their fellow employees. It has become challenging for management to “compete” with the level and volume of discourse among employees.

The list of devices and services routinely used by workers at every level is endless. The reality appears to be that for many employees the number of hours of usage in front of approved enterprise apps on managed enterprise devices is on the decline, unless new tablets and phones have been approved. The consumerization of IT appears to be very real, just by anecdotally observing the devices in use on public transportation, airports, and hotels. Certainly the conversation among people in suits over what to bring on trips is real and rapidly tilting towards “tablet for trips”, if not already there.

The frustration people have with IT to deliver or approve the use of services is readily apparent, just as the frustration IT has with people pushing to use insecure, unapproved, and hard to manage tools and devices. Whenever IT puts in a barrier, it is just a big rock in the information river that is an organization and information just flows around it. Forward-looking IT is working diligently to get ahead of this challenge, but the models used to reign in control of PCs and servers on corporate premises will prove of limited utility.

A new approach is needed to deal with this reality.

Transition versus disruption

The biggest risks organizations face is in thinking the transition to a new way of working will be just that, a transition, rather than a disruption. While individuals within an organization, particularly those that might be in senior management, will seek to smoothly transition from one style of work to another, the bulk of employees will switch quickly. Interns, new hires, or employees looking for an edge see these changes as the new normal or the only normal they’ve ever experienced. Our own experience with PCs is proof of how quickly change can take place.

In Only the Paranoid Survive, Andy Grove discussed breaking the news to employees of a new strategy at Intel only to find out that employees had long ago concluded the need for change—much to the surprise of management. The nature of a disruptive change in management is one in which management believes they are planning a smooth transition to new methods or technologies only to find out employees have already adopted them.

Today’s technology landscape is one undergoing a disruptive change in the enterprise—the shift to cloud based services, social interaction, and mobility. There is no smooth transition that will take place. Businesses that believe people will gradually move from yesterday’s modalities of work to these new ways will be surprised to learn that people are already working in these new ways. Technologists seeking solutions that “combine the best of both worlds” or “technology bridge” solutions will only find themselves comfortably dipping their toe in the water further solidifying an old approach while competitors race past them. The nature of disruptive technologies is the relentless all or nothing that they impose as they charge forward.

While some might believe that continuing to focus on “the desktop” will enable a smoother transition to mobile (or consumer) while the rough edges are worked out or capabilities catch up to what we already have, this is precisely the innovator’s dilemma – hunkering down and hoping things will not take place as quickly as they seem to be for some. In fact, to solidify this point of view many will point to a lack of precipitous decline or the mission critical nature in traditional ways of working. The tail is very long, but innovation and competitive edge will not come from the tail. Too much focus on the tail will risk being left behind or at the very least distract from where things are rapidly heading. Compatibility with existing systems has significant value, but is unlikely to bring about more competitive offerings, better products, or step-function improvements in execution.

Culture of continuous productivity

The culture of continuous productivity enabled by new tools is literally a rewrite of the past 30 years of management doctrine. Hierarchy, top-down decision making, strategic plans, static competitors, single-sided markets, and more are almost quaint views in a world literally flattened by the presence of connectivity, mobility, and data. The impact of continuous productivity can be viewed through the organization, individuals and teams, and the role of data.

The social and mobile aspects of work, finally, gain support of digital tools and with those tools the realization of just how much of nearly all work processes are intrinsically social. The existence and paramount importance of “document creation tools” as the nature of work appear, in hindsight, to have served as a slight detour of our collective focus. Tools can now work more like we like to work, rather than forcing us to structure our work to suit the tools. Every new generation of tools comes with promises of improvements, but we’ve already seen how the newest styles of work lead to improvements in our lives outside of work. Where it used to be novel for the person with a PC to use those tools to organize a sports team or school function, now we see the reverse and we see the tools for the rest of life being used to improve our work.

This existence proof makes this revolution different. We already experience the dramatic improvements in our social and non-work “processes”. With the support and adoption of new tools, just as our non-work lives saw improvements we will see improvements in work.

The cultural changes encouraged or enabled by continuous productivity include:

- Innovate more and faster. The bottom line is that by compressing the time between meaningful interactions between members of a team, we will go from problem to solution faster. Whether solving a problem with an existing product or service or thinking up a new one, the continuous nature of communication speeds up the velocity and quality of work. We all experience the pace at which changes outside work take place compared to the slow pace of change within our workplaces.

-

Flatten hierarchy. The difficulty in broad communication, the formality of digital tools, and restrictions on the flow of information all fit perfectly with a strict hierarchical model of teams. Managers “knew” more than others. Information flowed down. Management informed employees. Equal access to tools and information, a continuous multi-way dialog, and the ease and bringing together relevant parties regardless of place in the organization flattens the hierarchy. But more than that, it shines a light on the ineffectiveness and irrelevancy of a hierarchy as a command structure.

- Improve execution. Execution improves because members of teams have access to the interactions and data in real-time. Gone are the days of “game of telephone” where information needed to “cascade” through an organization only to be reinterpreted or even filtered by each level of an organization.

-

Respond to changes using telemetry / data. With the advent of continuous real-world usage telemetry, the debate and dialog move from deciding what the problems to be solved might be to solving the problem. You don’t spend energy arguing over the problem, but debating the merits of various solutions.

- Strengthen organization and partnerships. Organizations that communicate openly and transparently leave much less room for politics and hidden agendas. The transparency afforded by tools might introduce some rough and tumble in the early days as new “norms” are created but over time the ability to collaborate will only improve given the shared context and information base everyone works from.

- Focus on the destination, not the journey. The real-time sharing of information forces organizations to operate in real-time. Problems are in the here and now and demand solutions in the present. The benefit of this “pressure” is that a focus on the internal systems, the steps along the way, or intermediate results is, out of necessity, de-emphasized.

Organization culture change

Continuously productive organizations look and feel different from traditional organizations. As a comparison, consider how different a reunion (college, family, etc.) is in the era of Facebook usage. When everyone gets together there is so much more that is known—the reunion starts from shared context and “intimacy”. Organizations should be just as effective, no matter how big or how geographically dispersed.

Effective organizations were previously defined by rhythms of weekly, monthly and quarterly updates. These “episodic” connection points had high production values (and costs) and ironically relatively low retention and usage. Management liked this approach as it placed a high value on and required active management as distinct from the work. Tools were designed to run these meetings or email blasts, but over time these were far too often over-produced and tended to be used more for backward looking pseudo-accountability.

Looking ahead, continuously productive organizations will be characterized by the following:

- Execution-centric focus. Rather than indexing on the process of getting work done, the focus will shift dramatically to execution. The management doctrine of the late 20th century was about strategy. For decades we all knew that strategy took a short time to craft in reality, but in practice almost took on a life of its own. This often led to an ever-widening gap between strategy and execution, with execution being left to those of less seniority. When everyone has the ability to know what can be known (which isn’t everything) and to know what needs to be done, execution reigns supreme. The opportunity to improve or invent will be everywhere and even with finite resources available, the biggest failure of an organization will be a failure to act.

- Management framing context with teams deciding. Because information required discovery and flowed (deliberately) inefficiently management tasked itself with deciding “things”. The entire process of meetings degenerated into a ritualized process to inform management to decide amongst options while outside the meeting “everyone” always seemed to know what to do. The new role of management is to provide decision-making frameworks, not decisions. Decisions need to be made where there is the most information. Framing the problem to be solved out of the myriad of problems and communicating that efficiently is the new role of management.

- Outside is your friend. Previously the prevailing view was that inside companies there was more information than there was outside and often the outside was viewed as being poorly informed or incomplete. The debate over just how much wisdom resides in the crowd will continue and certainly what distinguishes companies with competitive products will be just how they navigate the crowd and simultaneously serve both articulated and unarticulated needs. For certain, the idea that the outside is an asset to the creation of value, not just the destination of value, is enabled by the tools and continuous flow of information.

- Employees see management participate and learn, everyone has the tools of management. It took practically 10 years from the introduction of the PC until management embraced it as a tool for everyday use by management. The revolution of social tools is totally different because today management already uses the socialplace tools outside of work. Using Twitter for work is little different from using Facebook for family. Employees expect management to participate directly and personally, whether the tool is a public cloud service or a private/controlled service. The idea of having an assistant participate on behalf of a manager with a social tool is as archaic as printing out email and typing in handwritten replies. Management no longer has separate tools or a different (more complete) set of books for the business, but rather information about projects and teams becomes readily accessible.

- Individuals own devices, organizations develop and manage IP. PCs were first acquired by individual tech enthusiasts or leading edge managers and then later by organizations. Over time PCs became physical assets of organizations. As organizations focused more on locking down and managing those assets and as individuals more broadly had their own PCs, there was a decided shift to being able to just “use a computer” when needed. The ubiquity of mobile devices almost from the arrival of smartphones and certainly tablets, has placed these devices squarely in the hands of individuals. The tablet is mine. And because it is so convenient for the rest of my life and I value doing a good job at work, I’m more than happy to do work on it “for free”. In exchange, organizations are rapidly moving to tools and processes that more clearly identify the work products as organization IP not the devices. Cloud-based services become the repositories of IP and devices access that through managed credentials.

Individuals and teams work differently

The new tools and techniques come together to improve upon the way individuals and teams interact. Just as the first communication tools transformed business, the tools of mobile and continuous productivity change the way interactions happen between individuals and teams.

- Sense and respond. Organizations through the PC era were focused on planning and reacting cycles. The long lead time to plan combined with the time to plan a reaction to events that were often delayed measurements themselves characterized “normal”. New tools are much more real-time and the information presented represents the whole of the information at work, not just samples and surveys. The way people will work will focus much more on everyone being sensors for what is going on and responding in real-time. Think of the difference between calling for a car or hailing a cab and using Uber or Lyft from either a consumer perspective or from the business perspective of load balancing cars and awareness of the assets at hand as representative to sensing and responding rather than planning.

- Bottom up and network centric. The idea of management hierarchy or middle management as gatekeepers is being broken down by the presence of information and connectivity. The modern organization working to be the most productive will foster an environment of bottom up—that is people closest to the work are empowered with information and tools to respond to changes in the environment. These “bottoms” of the organization will be highly networked with each other and connected to customers, partners, and even competitors. The “bandwidth” of this network is seemingly instant, facilitated by information sharing tools.

- Team and crowd spanning the internal and external. The barriers of an organization will take on less and less meaning when it comes to the networks created by employees. Nearly all businesses at scale are highly virtualized across vendors, partners, and customers. Collaboration on product development, product implementation, and product support take place spanning information networks as well as human networks. The “crowd” is no longer a mob characterized by comments on a blog post or web site, but can be structured and systematically tapped with rich demographic information to inform decisions and choices.

- Unstructured work rhythm. The highly structured approach to work that characterized the 20th century was created out of a necessity for gathering, analyzing, and presenting information for “costly” gatherings of time constrained people and expensive computing. With the pace of business and product change enabled by software, there is far less structure required in the overall work process. The rhythm of work is much more like routine social interactions and much less like daily, weekly, monthly staff meetings. Industries like news gathering have seen these radical transformations, as one example.

Data becomes pervasive (and big)

With software capabilities come ever-increasing data and information. While the 20th century enabled the collection of data and to a large degree the analysis of data to yield ever improving decisions in business, the prevalence of continuous data again transforms business.

- Sharing data continuously. First and foremost, data will now be shared continuously and broadly within organizations. The days when reports were something for management and management waited until the end of the week or month to disseminate filtered information are over. Even though financial data has been relatively available, we’re now able to see how products are used, trouble shoot problems customers might be having, understand the impact of small changes, and try out alternative approaches. Modern organizations will provide tools that enable the continuous sharing of data through mobile-first apps that don’t require connectivity to corporate networks or systems chained to desktop resources

- Always up to date. The implication of continuously sharing information means that everyone is always up to date. When having a discussion or meeting, the real world numbers can be pulled up right then and there in the hallway or meeting room. Members of teams don’t spend time figuring out if they agree on numbers, where they came from or when they were “pulled”. Rather the tools define the numbers people are looking at and the data in those tools is the one true set of facts.

- Yielding best statistical approach informed by telemetry (induction). The notion that there is a “right” answer is antiquated as the printed report. We can now all admit that going to a meeting with a printed out copy of “the numbers” is not worth the debate over the validity or timeframe of those numbers (“the meeting was rescheduled, now we have to reprint the slides.”) Meetings now are informed by live data using tools such as Mixpanel or live reporting from Workday, Salesforce and others. We all know now that “right” is the enemy of “close enough” given that the datasets we can work with are truly based on census and not surveys. This telemetry facilitates an inductive approach to decision-making.

- Valuing more usage. Because of the ability to truly understand the usage of products—movies watched, bank accounts used, limousines taken, rooms booked, products browsed and more—the value of having more people using products and services increases dramatically. Share matters more in this world because with share comes the best understanding of potential growth areas and opportunities to develop for new scenarios and new business approaches.

New generation of productivity tools, examples and checklist

Bringing together new technologies and new methods for management has implications that go beyond the obvious and immediate. We will all certainly be bringing our own devices to work, accessing and contributing to work from a variety of platforms, and seeing our work take place across organization boundaries with greater ease. We can look very specifically at how things will change across the tools we use, the way we communicate, how success is measured, and the structure of teams.

Tools will be quite different from those that grew up through the desktop PC era. At the highest level the implications about how tools are used are profound. New tools are being developed today—these are not “ports” of existing tools for mobile platforms, but ideas for new interpretations of tools or new combinations of technologies. In the classic definition of innovator’s dilemma, these new tools are less functional than the current state-of-the-art desktop tools. These new tools have features and capabilities that are either unavailable or suboptimal at an architectural level in today’s ubiquitous tools. It will be some time, if ever, before new tools have all the capabilities of existing tools. By now, this pattern of disruptive technologies is familiar (for example, digital cameras, online reading, online videos, digital music, etc.).

The user experience of this new generation of productivity tools takes on a number of attributes that contrast with existing tools, including:

- Continuous v. episodic. Historically work took place in peaks and valleys. Rough drafts created, then circulated, then distributed after much fanfare (and often watering down). The inability to stay in contact led to a rhythm that was based on high-cost meetings taking place at infrequent times, often requiring significant devotion of time to catching up. Continuously productive tools keep teams connected through the whole process of creation and sharing. This is not just the use of adjunct tools like email (and endless attachments) or change tracking used by a small number of specialists, but deep and instant collaboration, real-time editing, and a view that information is never perfect or done being assembled.

- Online and shared information. The old world of creating information was based on deliberate sharing at points in time. Heavyweight sharing of attachments led to a world where each of us became “merge points” for work. We worked independently in silos hoping not to step on each other never sure where the true document of record might be or even who had permission to see a document. New tools are online all the time and by default. By default information can be shared and everyone is up to date all the time.

- Capture and continue The episodic nature of work products along with the general pace of organizations created an environment where the “final” output carried with it significant meaning (to some). Yet how often do meetings take place where the presenter apologizes for data that is out of date relative to the image of a spreadsheet or org chart embedded in a presentation or memo? Working continuously means capturing information quickly and in real-time then moving on. There are very few end points or final documents. Working with customers and partners is a continuous process and the information is continuous as well.

- Low startup costs. Implementing a new system used to be a time consuming and elaborate process viewed as a multi-year investment and deployment project. Tools came to define the work process and more critically make it impossibly difficult to change the work process. New tools are experienced the same way we experience everything on the Internet—we visit a site or download an app and give it a try. The cost to starting up is a low-cost subscription or even a trial. Over time more features can be purchased (more controls, more depth), but the key is the very low-cost to begin to try out a new way to work. Work needs change as market dynamics change and the era of tools preventing change is over.

- Sharing inside and outside. We are all familiar with the challenges of sharing information beyond corporate boundaries. Management and IT are, rightfully, protective of assets. Individuals struggle with the basics of getting files through firewalls and email guards. The results are solutions today that few are happy with. Tools are rapidly evolving to use real identities to enable sharing when needed and cross-organization connections as desired. Failing to adopt these approaches, IT will be left watching assets leak out and workarounds continue unabated.

- Measured enterprise integration. The PC era came to be defined at first by empowerment as leading edge technology adopters brought PCs to the workplace. The mayhem this created was then controlled by IT that became responsible to keep PCs running, information and networks secure, and enforce consistency in organizations for the sake of sharing and collaboration. Many might (perhaps wrongly) conclude that the consumerization wave defined here means IT has no role in these tasks. Rather the new era is defined by a measured approach to IT control and integration. Tools for identity and device management will come to define how IT integrates and controls—customization or picking and choosing code are neither likely nor scalable across the plethora of devices and platforms that will be used by people to participate in work processes. The net is to control enterprise information flow, not enterprise information endpoints.

- Mobile first. An example of a transition between the old and new, many see the ability to view email attachments on mobile devices as a way forward. However, new tools imply this is a true bridge solution as mobility will come to trump most everything for a broad set of people. Deep design for architects, spreadsheets for analysts, or computation for engineers are examples that will likely be stationary or at least require unique computing capabilities for some time. We will all likely be surprised by the pace at which even these “power” scenarios transition in part to mobile. The value of being able to make progress while close to the site, the client, or the problem will become a huge asset for those that approach their professions that way.

- Devices in many sizes. Until there is a radical transformation of user-machine interaction (input, display), it is likely almost all of us will continue to routinely use devices of several sizes and those sizes will tend to gravitate towards different scenarios (see http://blog.flurry.com/bid/99859/The-Who-What-and-When-of-iPhone-and-iPad-Usage), though commonality in the platforms will allow for overlap. This overlap will continue to be debated as “compromise” by some. It is certain we will all have a device that we carry and use almost all the time, the “phone”. A larger screen device will continue to better serve many scenarios or just provide a larger screen area upon which to operate. Some will find a small tablet size meeting their needs almost all of the time. Others will prefer a larger tablet, perhaps with a keyboard. It is likely we will see somewhat larger tablets arise as people look to use modern operating systems as full-time replacements for existing computing devices. The implications are that tools will be designed for different device sizes and input modalities.

It is worth considering a few examples of these tools. As an illustration, the following lists tools in a few generalized categories of work processes. New tools are appearing almost every week as the opportunity for innovation in the productivity space is at a unique inflection point. These examples are just a few tools that I’ve personally had a chance to experience—I suspect (and hope) that many will want to expand these categories and suggest additional tools (or use this as a springboard for a dialog!)

- Creation. Quip, Evernote, Paper, Haiku Deck, Lucidchart

- Storage and Sharing. Box, Dropbox, Hightail

- Reporting. Mixpanel, Quantifind

- Communications. WhatsApp, Anchor, Voxer

- Tracking. Asana, Todoist, Relaborate

- Training. Udacity, Thinkful, Codeacademy

The architecture and implementation of continuous productivity tools will also be quite different from the architecture of existing tools. This starts by targeting a new generation of platforms, sealed-case platforms.

The PC era was defined by a level of openness in architecture that created the opportunity for innovation and creativity that led to the amazing revolution we all benefit from today. An unintended side-effect of that openness was the inherent unreliability over time, security challenges, and general futzing that have come to define the experience many lament. The new generation of sealed case platforms—that is hardware, software, and services that have different points of openness, relative to previous norms in computing, provide for an experience that is more reliable over time, more secure and predictable, and less time-consuming to own and use. The tradeoff seems dramatic (or draconian) to those versed in old platforms where tweaking and customizing came to dominate. In practice the movement up the stack, so to speak, of the platform will free up enormous amounts of IT budget and resources to allow a much broader focus on the business. In addition, choice, flexibility, simplicity in use, and ease of using multiple devices, along with a relative lack of futzing will come to define this new computing experience for individuals.

The sealed case platforms include iOS, Android, Chromebooks, Windows RT, and others. These platforms are defined by characteristics such as minimizing APIs that manipulate the OS itself, APIs that enforce lower power utilization (defined background execution), cross-application security (sandboxing), relative assurances that apps do what they say they will do (permissions, App Stores), defined semantics for exchanging data between applications, and enforced access to both user data and app state data. These platforms are all relatively new and the “rules” for just how sealed a platform might be and how this level of control will evolve are still being written by vendors. In addition, devices themselves demonstrate the ideals of sealed case by restricting the attachment of peripherals and reducing the reliance on kernel mode software written outside the OS itself. For many this evolution is as controversial as the transition automobiles made from “user-serviceable” to electronic controlled engines, but the benefits to the humans using the devices are clear.

Building on the sealed case platform, a new generation of applications will exhibit a significant number of the following attributes at the architecture and implementation level. As with all transitions, debates will rage over the relative strength or priority of one or more attributes for an app or scenario (“is something truly cloud” or historically “is this a native GUI”). Over time, if history is any guide, the preferred tools will exhibit these and other attributes as a first or native priority, and de-prioritize the checklists that characterized the “best of” apps for the previous era.

The following is a checklist of attributes of tools for continuous productivity:

- Mobile first. Information will be accessed and actions will be performed mobile first for a vast majority of both employees and customers. Mobile first is about native apps, which is likely to create a set of choices for developers as they balance different platforms and different form factors.

- Cloud first. Information we create will be stored first in the cloud, and when needed (or possible) will sync back to devices. The days of all of us focusing on the tasks of file management and thinking about physical storage have been replaced by essentially unlimited cloud storage. With cloud-storage comes multi-device access and instant collaboration that spans networks. Search becomes an integral part of the user-experience along with labels and meta-data, rather than physical hierarchy presenting only a single dimension. Export to broadly used interchange formats and printing remain as critical and archival steps, but not the primary way we share and collaborate.

- User experience is platform native or browser exploitive. Supporting mobile apps is a decision to fully use and integrate with a mobile platform. While using a browser can and will be a choice for some, even then it will become increasingly important to exploit the features unique to a browser. In all cases, the usage within a customer’s chosen environment encourages the full range of support for that platform environment.

- Service is the product, product is the service. Whether an internal IT or a consumer facing offering, there is no distinction where a product ends and a continuously operated and improving service begins. This means that the operational view of a product is of paramount importance to the product itself and it means that almost every physical product can be improved by a software service element.

- Tools are discrete, loosely coupled, limited surface area. The tools used will span platforms and form factors. When used this way, monolithic tools that require complex interactions will fall out of favor relative to tools more focused in their functionality. Doing a smaller set of things with focus and alacrity will provide more utility, especially when these tools can be easily connected through standard data types or intermediate services such as sharing, storage, and identity.

- Data contributed is data extractable. Data that you add to a service as an end-user is easily extracted for further use and sharing. A corollary to this is that data will be used more if it can also be extracted a shared. Putting barriers in place to share data will drive the usage of the data (and tool) lower.

- Metadata is as important as data. In mobile scenarios the need to search and isolate information with a smaller user interface surface area and fewer “keystrokes” means that tools for organization become even more important. The use of metadata implicit in the data, from location to author to extracted information from a directory of people will become increasingly important to mobile usage scenarios.

- Files move from something you manage to something you use when needed. Files (and by corollary mailboxes) will simply become tools and not obsessions. We’re all seeing the advances in unlimited storage along with accurate search change the way we use mailboxes. The same will happen with files. In addition, the isolation and contract-based sharing that defines sealed platforms will alter the semantic level at which we deal with information. The days of spending countless hours creating and managing hierarchies and physical storage structures are over—unlimited storage, device replication, and search make for far better alternatives.

- Identity is a choice. Use of services, particularly consumer facing services, requires flexibility in identity. Being able to use company credentials and/or company sign-on should be a choice but not a requirement. This is especially true when considering use of tools that enable cross-organization collaboration. Inviting people to participate in the process should be as simple as sending them mail today.

- User experience has a memory and is aware and predictive. People expect their interactions with services to be smart—to remember choices, learn preferences, and predict what comes next. As an example, location-based services are not restricted to just maps or specific services, but broadly to all mobile interactions where the value of location can improve the overall experience.

- Telemetry is essential / privacy redefined. Usage is what drives incremental product improvements along with the ability to deliver a continuously improving product/service. This usage will be measured by anonymous, private, opt-in telemetry. In addition, all of our experiences will improve because the experience will be tailored to our usage. This implies a new level of trust with regard to the vendors we all use. Privacy will no doubt undergo (or already has undergone) definitional changes as we become either comfortable or informed with respect to the opportunities for better products.

- Participation is a feature. Nearly every service benefits from participation by those relevant to the work at hand. New tools will not just enable, but encourage collaboration and communication in real-time and connected to the work products. Working in one place (document editor) and participating in another (email inbox) has generally been suboptimal and now we have alternatives. Participation is a feature of creating a work product and ideally seamless.

- Business communication becomes indistinguishable from social. The history of business communication having a distinct protocol from social goes back at least to learning the difference between a business letter and a friendly letter in typing class. Today we use casual tools like SMS for business communication and while we will certainly be more respectful and clear with customers, clients, and superiors, the reality is the immediacy of tools that enable continuous productivity will also create a new set of norms for business communication. We will also see the ability to do business communication from any device at any time and social/personal communication on that same device drive a convergence of communication styles.

- Enterprise usage and control does not make things worse. In order for enterprises to manage and protect the intellectual property that defines the enterprise and the contribution employees make to the enterprise IP, data will need to be managed. This is distinctly different from managing tools—the days of trying to prevent or manage information leaks by controlling the tools themselves are likely behind us. People have too many choices and will simply choose tools (often against policy and budgets) that provide for frictionless work with coworkers, partners, customers, and vendors. The new generation of tools will enable the protection and management of information that does not make using tools worse or cause people to seek available alternatives. The best tools will seamlessly integrate with enterprise identity while maintaining the consumerization attributes we all love.

What comes next?

Over the coming months and years, debates will continue over whether or not the new platforms and newly created tools will replace, augment, or see occasional use relative to the tools with which we are all familiar. Changes as significant as those we are experiencing right now happen two ways, at first gradually and then quickly, to paraphrase Hemingway. Some might find little need or incentive to change. Others have already embraced the changes. Perhaps those right now on the cusp, realize that the benefits of their new device and new apps are gradually taking over their most important work and information needs. All of these will happen. This makes for a healthy dialog.

It also makes for an amazing opportunity to transform how organizations make products, serve customers, and do the work of corporations. We’re on the verge of seeing an entire rewrite of the management canon of the 20th century. New ways of organizing, managing, working, collaborating are being enabled by the tools of the continuous productivity paradigm shift.

Above all, it makes for an incredible opportunity for developers and those creating new products and services. We will all benefit from the innovations in technology that we will experience much sooner than we think.

–Steven Sinofsky

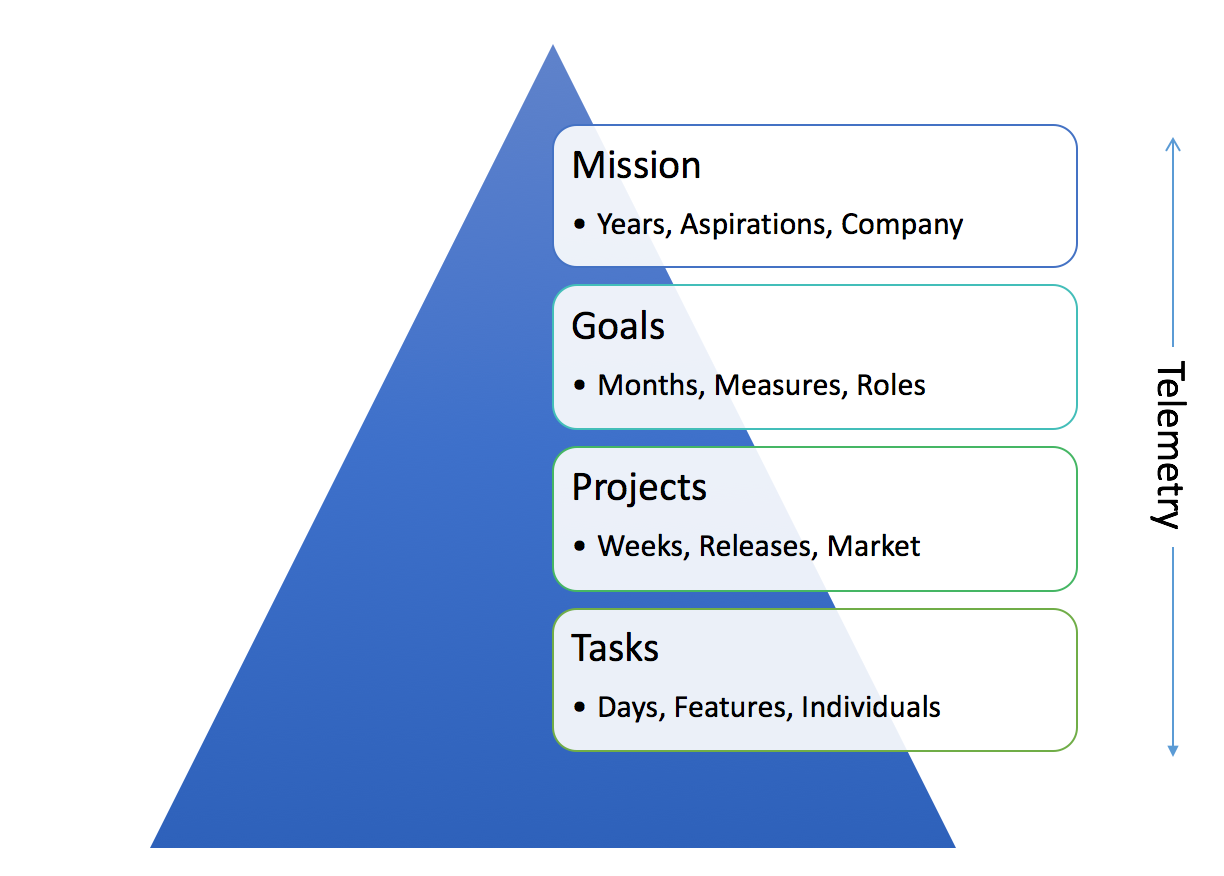

A key role of product management (PM), whether as the product-focused founder (CEO, CTO) or the PM leader, is making sure product development efforts are focused. But what does it mean to be focused? This isn’t always as clear as it could be for a team. While everyone loves focus, there’s an equal love for agility, action, and moving “forward”. Keeping the trains running is incredibly important, but just as important and often overlooked is making sure the destination is clear.

A key role of product management (PM), whether as the product-focused founder (CEO, CTO) or the PM leader, is making sure product development efforts are focused. But what does it mean to be focused? This isn’t always as clear as it could be for a team. While everyone loves focus, there’s an equal love for agility, action, and moving “forward”. Keeping the trains running is incredibly important, but just as important and often overlooked is making sure the destination is clear.

Decision-making is one of the most difficult skills to master as a manager. A startup CEO literally sees a constant stream of decisions to be made: from hiring and firing, to Android or iOS, all the way to Lack or Billy. As the company grows to 10–20 people (usually mostly engineering) the bonds and shared experiences continue support decision-making at the micro-level. Once a team grows larger there is a need for management and delegation. While growth is a positive it also a stressful time for the company and founder/CEO.

Decision-making is one of the most difficult skills to master as a manager. A startup CEO literally sees a constant stream of decisions to be made: from hiring and firing, to Android or iOS, all the way to Lack or Billy. As the company grows to 10–20 people (usually mostly engineering) the bonds and shared experiences continue support decision-making at the micro-level. Once a team grows larger there is a need for management and delegation. While growth is a positive it also a stressful time for the company and founder/CEO.

Micromanagement can be a reflection of a manager’s feedback and concerns about progress. Empowerment can create a detached or worried manager. Threading the needle between delegation and micromanagement is central to the relationship between a manager and a report. How do you balance this as either a manager or employee?

Micromanagement can be a reflection of a manager’s feedback and concerns about progress. Empowerment can create a detached or worried manager. Threading the needle between delegation and micromanagement is central to the relationship between a manager and a report. How do you balance this as either a manager or employee? As a manager, big company or small, the opportunities to lead are everywhere. Too often though we can fail to lead and fall into the trap of editing the work of others–critiquing, tweaking, or otherwise mucking with what is discussed or delivered, rather than stepping back and considering if we are truly improving on the work or just imprinting upon the work, or if we are empowering or micromanaging.

As a manager, big company or small, the opportunities to lead are everywhere. Too often though we can fail to lead and fall into the trap of editing the work of others–critiquing, tweaking, or otherwise mucking with what is discussed or delivered, rather than stepping back and considering if we are truly improving on the work or just imprinting upon the work, or if we are empowering or micromanaging.