Archive for February 2015

That First Sales or Marketing Hire

One of the biggest changes for an early-stage and growing company is when hiring transitions from technical/product founders to the first sales or marketing hires. It is an exciting time of course but also one that can be very stressful. As much as that can be the case, there are a few patterns and practices one can follow to successfully cross that chasm or at the very least reduce the risk to the same as any technical hire.

One of the biggest changes for an early-stage and growing company is when hiring transitions from technical/product founders to the first sales or marketing hires. It is an exciting time of course but also one that can be very stressful. As much as that can be the case, there are a few patterns and practices one can follow to successfully cross that chasm or at the very least reduce the risk to the same as any technical hire.

It goes without saying that the challenge is rooted in learning how to recognize and evaluate talented people that possess talents and skills that you do not have and really can’t relate to from an experience level. Quite a few roles in companies are going to be “close” or adjacent to your own skill set, speaking from the perspective of a technical founder. If you’re an engineer then QA or product management aren’t far off from what you do on a daily basis. If you tilt towards product management, you’re interactions with designers are perfectly natural. In fact for technical founders the spectrum from design to product management to engineering and then QA all feel like your wheelhouse.

Branching out further to sales, marketing, communications, business development, customer service, operations, supply chain, manufacturing, finance, and more can get uncomfortable very quickly. I remember the first time I had to interview a marketing person and I realized I didn’t even know what questions I should ask to do the interview. Yet, I had worked with marketing closely for many years. Fortunately, I had a candidate pipeline and an interview loop of experienced interviewers to draw from. That’s not alway the case with a startup’s first hires.

The following are four challenges worth considering and a step you can take to mitigate the challenges if you find yourself in this spot.

Look only within your network. When sourcing your first potential sales or marketing hire, you might tend to tap into your network the same way you would for an engineering hire. You might have a very broad network but it might not be a first person network. For example with engineering you might know people from the same school program or projects you worked on or are deeply familiar with. But with sales and marketing you probably lack that much common context and your network might reflect people you came across with in work or projects, but not necessarily worked with in the same way you would have with technical hires. You might be worried about taking too much time to source candidates or concerned that you will burn a lot of time on introductions and people you don’t “know” well. Approach. The first step in a breakthrough hire process is to make sure you cast a wide net and tap into other networks. This process itself is an investment in the future as you will broaden your network in a new domain.

Define the job by way you know from the outside. Walk a mile in other’s shoes is an age-old expression and is very fitting for your first sales or marketing hire. Your initial job description for a job you never done might be taken from another company or might be based on your view of what the job needs to get done. The challenge is that your view of what needs to get done is informed by your own “outsider” view of what a job you haven’t done before might mean. Being a sales or marketing person is vastly different from what it looks like from the outside, looking in. If you haven’t done the job you tend to think of the job through the lens of outputs rather than the journey from input to output. Most jobs are icebergs and the real work is the 90% under water. Until you’ve watched and worked with an enterprise sale end to end or developed and executed on a consumer go to market plan, your view of what the job looks like might be a sales presentation or SEO. Getting to those deliverables is a whole different set of motions. Approach. Find a way to have a few “what do you do” conversations with senior people in the job function. Maybe take some time to ask them to define for you what they think the steps would be to get to the outcome you are looking for, rather than to discuss the outcome. These “what would it take” conversations will help you to craft a skills assessment and talent fit.

Hire too senior or too junior. Gauging the seniority of a candidate and matching that to the requirement for the role are often quite tricky early on. In the conversations I’ve had I tend to see founders head to one extreme or another. Some founders take the outcome or deliverable they might want (white paper, quota) and work backwards to find a hire to “execute” on that. Some take the other extreme and act on the basis of not knowing so bringing in a senior person to build out the whole system. The reality is that for a new company you often are best off with someone in the middle. Why is that? If you hire to too junior the person will need supervision on a whole range of details you haven’t done before. This gets back to defining the job based on what you know—your solution set will be informed only by the experience you have had. If you hire someone too senior then they will immediately want to hire in the next round of management. You will quickly find that one hire translates into three and you’re scaling faster than you’re growing. I once talked to a company that was under ten engineers and hired a very senior marketing leader with domain experience who then subsequently spent $200K on consulting to develop a “marketing plan”. Yikes. Approach. Building on the knowledge you gained by casting a wide net and by taking the time to learn the full scope of work required, aim for the right level of hire that will “do the work” while “scaling the team”.

Base feedback on too small a circle. Once you have a robust job description and candidate flow and ways to evaluate, it is not uncommon to “fall back” on a small circle of people to get feedback on and evaluate the candidate. You might not want to take up time of too many people or you might think that it is tricky for too many people to evaluate a candidate. At the other end you might want these first hires to be a consensus based choice among a group that collectively is still learning these multi-disciplinary ropes. Culture fit is always a huge part of hiring, especially early on, but you’re also concerned about bringing in a whole new culture (a “sales culture” or “business culture”) and that contributes to the desire to keep things contained. Approach. Getting feedback from at least one trusted senior person with experience and success making these specific hires is critical. You can tap into your board or investors or network, but be sure to lean on those supporting you for some validation and verification.

One interesting note is that these challenges and approaches aren’t unique to startups. It turns out these follow similar patterns in large companies as well as you rise from engineering/product to business or general management. While you might think in a big company the support network insulates you from these challenges, I’ve seen (and experienced personally) all of the above.

The first sales or marketing hires can be pretty stressful for any technologist. Branching out to hire and manage those that rely more than you on the other side of their brain is a big opportunity for growth and development not only for the company but for you personally. It is a great time to step back and seek out support, advice, and counsel.

Patience, IoT Is the New “Electronic”

The “Internet of Things” or IoT is cool. I know this because everyone tells everyone else how cool it is. Ask anyone and they will give you their own definition of what IoT means and why it is cool. That’s proof we are using a buzzword or are in a hype-cycle.

The “Internet of Things” or IoT is cool. I know this because everyone tells everyone else how cool it is. Ask anyone and they will give you their own definition of what IoT means and why it is cool. That’s proof we are using a buzzword or are in a hype-cycle.

Much is at stake to benefit from, contribute to, or even control this next, next-generation of computing. If a company benefitted from 300 million PCs a year, that’s quite cool. If another company benefitted from 1 billion smartphones a year, then that’s pretty cool.

You know what is really cool, benefitting from 75 billion devices. That certainly explains the enthusiasm for the catch phrase.

Missing out on this wave is uncool. Just take a look at the CNBC screen shot to the left. That’s what we talked about in the Digital Innovation class at HBS last week and what motivated this post.

In an effort to quantify the opportunity, claim leadership, or just be included amongst those who “get it” we are all collectively missing the fact that we really don’t know how this will play out in any micro sense. It is safe to say everything will be connected to the internet. That’s about it. As Benedict Evans says, counting connected devices is a lot like counting how many electric motors are in your home. In the first days this was cool. Today, that seems silly. Benedict’s excellent post also goes into details asking many good questions about what being connected might mean and here I enhance our in-class discussion.

One way to view the history of “devices” is through two generations in the 20th century. For the first 50 years we had “analog motor” devices that replaced manual mechanical devices. This was the age of convenience brought by motors of all kinds from giant gas motors that produced electricity to tiny DC motors that powered household gadgets and everything in between. People very quickly learned the benefits of using motors to enhance manual effort. Though if you don’t think it was a generational shift, consider the reactions to the first labor saving home appliances (see Disney’s Carousel of Progress).

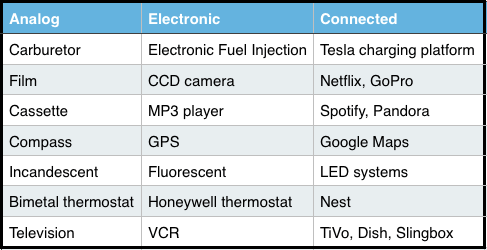

The next 50 years was about “digital electronics” which began with the diode, then the transistor, and then the microprocessor. What is amazing about this transition is how many decades past before the full transformation took place. Early on electronics replaced analog variants. Often these were viewed as luxuries at best, or inferior “gadgets” at worse. I recall my father debating with a car dealer the merits of “electronic fuel injection”. Many of us reading this certainly recall (or still believe) the debate over the quality of digital music relative to analog LP and cassette. Interestingly, the benefit we all experience today of size, weight, power consumption, portability, and more took years to gain acceptance. We used to think about “repairing” a VCR and how awful it was that you could not repair a DVD player. Go figure. The key innovation insight is that the benefits of electronics took decades to play out and were not readily apparent to all at the start.

We find ourselves at the start of a generation of invention where everything is connected. We are at the early stages where we are connecting things that we can connect, just like we added motors to replace the human turning the crank on a knitting loom. Some inventions have the magic of the portable radio—freedom and portability. Some seem as gimmicky as that blender.

Here are a few things we all know and love today that have already been transformed by “first generation” connectivity:

For the next few years, thousands of innovators will embark on the idea maze (Chris Dixon summarizes Balaji Srinivasan’s lecture). This is not just about product-market fit, but about much more basic questions. Every generational change in technology introduces a phase of crazy inventing, and that is where we are today with IoT.

This means that for the next couple of years most every product or invention, at first glance, might seem super cool (to some) and crazy to most everyone else. Then after a little use or analysis, more sober minds will prevail. The journey through the idea maze and engineering realities will continue.

This also means that every “thing” introduced will be met with skepticism of the broader, less tech-enthused, market (like our diverse classroom). Every introduction will seem more expensive, more complex, more superfluous than what is currently in use. In fact it is likely that even the ancillary benefits of being connected will be lost on most everyone.

That almost reads like the definition of innovator’s dilemma. Nothing sums this up more than how people talk about smart “watches”, connected thermostats, or robots. One either immediately sees the utility of strapping to your wrist a sub-optimal smartphone you have to charge midday or you ask why you can’t just look at your phone’s lock screen for the time. One looks at Nest thermostat and asks why paying 10X for the luxury of having a professional HVAC installer get stumped or having to “train” something you set and forget is such a good idea.

We find ourselves in the midst of a generational change in the technology base upon which everything is built. It used to be that owning an “electric” or “electronic” thing sounded modern and cool, well because they were so unique. That’s why adding “connected” or “smart” to a product is going to sound about as silly as saying “transistor radio” or “electronic oven”.

Every thing will be connected. The thing is we, collectively, have neither mastered connecting a thing without some downside (cost, weight, complexity) nor even figured out what we would do when something is connected. What are the equivalents of size, weight, reliability, ease of manufacturing, and more when it comes to connectivity? Today we do the “obvious” such as use the cloud for remote relay, access, storage. We write an app to control something over WiFi rather than build in a physical user interface. We collect and analyze data to inform usage or future products. There is more to come. How will devices be connected to each other? How will third parties improve the usage of things and just make them better? Where do we put the “smarts” in a thing when we have thousands of things? How might we find we are safer, healthier, faster, and even just happier?

We just don’t know yet. What we do know is that a lot of entrepreneurs and innovators across companies are going to try things out and incrementally get us to a new connected world, which in a few years will just be the world.

The Internet of Things is not about the things or even the platform the same way we thought about motors or microprocessors. The big winners in IoT will be thinking about an entirely different future, not just connecting to things we already use today in ways we already use them.