Archive for January 2014

Don’t ban email—change how you work!

How often do you hear things like “let’s ban email”, “no more attachments”, “death to PowerPoint decks”, “we’re going paperless”, “meeting free friday” or one of dozens of “bans” designed to do away with something that has become annoying or inefficient in the workplace? If you’re around long enough you can see just about anything cross over from innovative new tool to candidate to be banned. The problem is that banning a tool (or process) in an attempt at simplification never solves the problem. Rather, one should to look at a different approach, an approach that focuses on the work not the tool or process.

How often do you hear things like “let’s ban email”, “no more attachments”, “death to PowerPoint decks”, “we’re going paperless”, “meeting free friday” or one of dozens of “bans” designed to do away with something that has become annoying or inefficient in the workplace? If you’re around long enough you can see just about anything cross over from innovative new tool to candidate to be banned. The problem is that banning a tool (or process) in an attempt at simplification never solves the problem. Rather, one should to look at a different approach, an approach that focuses on the work not the tool or process.

What’s the problem?

It is well understood that new technologies go through an adoption curve. In the classic sense it is a normal distribution as described by researchers in the 1950’s. More recently and generally cited in the software world is Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm which describes a slightly different path. These models all share a common view of a group of early adopters followed by a growing base of users of a technology.

While adoption is great, we are all too used to experiencing excess enthusiasm for new technologies. As a technology spreads, so does the enthusiasm. Invariably some folks use the technology to the the point of abusing it. From reply all to massive attachments to elaborate scorecards with more dimensions than anyone can understand, the well-intentioned enthusiastic user turns a game-changing tool into a distraction or worse.

Just as with adoption curves, once can create a conceptual “irritation curve” and overlay it with adoption. Of course what is pictured below is not based on any data or specific to any technology, but consistent with our collective anecdotal point of view.

The key is that at some point the adoption of a new product crosses the chasm and becomes widely used within a company. While there is a time delay, sometimes years, at some point the perceived “abuse” of the technology causes a cross-over where for some set of people the irritation outpaces the utility. Just as there are early adopters, there are also irritation canaries who are the first to feel the utility of the new technology declining with increased usage.

We see this same dynamic not just for tools, but for business processes as well. That status report, dashboard, or checkin mail all start off as well-intentioned and then after some period of time the “just one more thing” or spreading over-usage at all levels of a team turn a positive into a burden.

Then at some point people start to reject the tool or process. Some even call for an outright ban or elimination.

What’s the solution?

The way to break the cycle is to dive into the actual work and not the tool. Historically, tools fade away when the work process changes.

It is tough to find examples of popular tools and processes that were simply banned that did not make a comeback. Companies that ban meetings or email on fridays just have more meetings and email on monday-thursday. I’ve personally seen far too many examples of too much information crammed on to a page (smaller fonts or margins anyone) or slides that need to be printed rather than projected in an effort to squeeze more on a page when there are forced limits on story-telling.

On the other hand, from voice mail to fax machines to pagers to typewriters to voice calls we have examples of tools that achieve high and subsequently irritating usage levels can and do go away because new tools take over. If you were around for any of those then you know that people called for them to be banned and yet they continued, until one day we all just stopped using them.

A favorite historical example is a company that told me they removed all the typewriters when PCs were introduced. The company was trying to save time because typewriters were much more difficult to use than PCs with printers (of course!). The problem was immediately seen by those responsible for the workflows in the company–all of a sudden no one could fill out an expense report, transfer to another department, or pay an invoice. All of these work processes, the blizzard of paperwork that folks thought were caused by typewriters, were rendered inoperable. These processes all required a typewriter to fill out the form and the word processors had no way of navigating pre-printed forms in triplicate. Of course what needed to happen was not a pre-printed form that worked in a word processor (what the administrative folks asked for), but a rethinking of the workflow that could be enabled by new tools (what management needed to do).

This sort of rethinking of work is what is so exciting right now. It is fair to say that the established, and overloaded, desktop work-processes and tools of the past 20 years are being disrupted by a new generation of tools. In addition to re-imagining how work can be done to avoid the problems of the past, these tools are built on a modern, mobile, cloud, and social infrastructure.

For example, Tom Preston-Werner, co-founder of GitHub, tells a great story about the motivations for GitHub that echoes my own personal experience. As software projects grew the communication of code changes/checkins generate an overwhelming blizzard of mail. Rather than just shut down these notifications and hope for the best, what was needed was a better tool so he invented one.

At Asana, Dustin Moskovitz, tells of their goal to eliminate email for a whole set of tracking and task management efforts. We’ve all seen examples of the collaborative process playing out poorly by using email. There’s too much email and no ability to track and manage the overall work using the tool. Despite calls to ban the process, what is really needed is a new tool. So Asana is one of many companies working to build tools that are better suited to the work than one we currently all collectively seem to complain about.

Just because a tool is broadly deployed doesn’t mean it is the right or best way to work.

We’re seeing new tools that are designed from the ground up to enable new ways of working and these are based on the learning from the past two decades of tool abuse.

What are some warning signs for teams and managers?

It is easy to complain about a tool. Sometimes the complaints are about the work itself and the tool is just the scapegoat. There’s value in looking at tool usage or process creation from a team or management perspective. My own experience is that the clarion calls to ban a tool or process have some common warning signs that are worth keeping an eye out for as the team might avoid the jump to banning something, which we know won’t work.

- Who is setting expectations for work product / process? If management is mandating the use of a tool the odds of a rebellion against it go up. As a general rule, the more management frames the outcome and the less the mechanism for the outcome the more tolerance there will be for the tool. Conversely, if the team comes up with a way of working that is hard for outsiders to follow or understand, it is likely to see pushback from partners or management. However, if it is working and the goal is properly framed then it seems harmless to keep using a tool. Teams should be allowed to use or abuse tools as they see fit so long as the work is getting done, no matter how things might look from outside.

- Does the work product benefit the team doing the work or the person asking? A corollary to above is the tool or process that is mandated but seems to have no obvious benefit is usually a rebellion in-waiting. Document production is notorious for this. From status reports to slides to spreadsheets, the specification by management to create ever more elaborate “work products” for the benefit of management invariably lead to a distaste for the tool. It is always a good idea for management to reduce the need to create work, tools, and processes where the benefit accrues to management exclusively. Once again, the members of the team will likely start to feel like banning the use of the tool is the only way to ease the overload or tax.

- Do people get evaluated (explicitly or implicitly) on the quality of the work product/process or the end-result? A sure-fire warning sign to the looming distaste of a tool or process is when a given work product becomes a goal or is itself measured. Are people measured by the completion of a report? Does someone look at how many email notifications get generated by someone? Does someone get kudos for completing a template about the group’s progress? All of these are tools that might be considered valuable in the course of achieving the actual goals of the team, but are themselves the path along the way. Are your status reports getting progressively more elaborate? Are people creating email rules to shunt email notifications to a folder? Are people starting to say “gosh I must have missed that”? All of those are warning signs that there is an impending pushback against the tool or process.

- What doesn’t get done if you just stop? The ultimate indicator for a need to change a tool or process is to play out what would happen if you really did ban it. We all know that banning email is really impractical. There are simply too many exceptions and that is exactly the point. Many tools can have a role in the modern workplace. Banning a tool in isolation of the work never works. Taking a systematic look at the work required that uses a tool, those that use the tool, and those that benefit from the output is the best way to approach the desire to use the most appropriate toolset in the workplace.

What tools need to change in your organization? What work needs to change so that the team doesn’t need to rely on inappropriate or inefficient tools?

–Steven (@stevesi)

PS: As I finished writing this post, this Forrester report came across twitter: Reality Check: Enterprise Social Does Not Stem Email Overload.

Why was 1984 not really like “1984”, for me

For me, 1984 was the year of Van Halen’s wonderful [sic] album, The Right Stuff, and my second semester of college. It would also prove to be a time of enlightenment for me and computing. On this 30th anniversary of the Apple Macintosh on January 25 and the Superbowl commercial on January 22. I wanted to share my own story of the way the introduction of the Macintosh profoundly changed my path in life.

For me, 1984 was the year of Van Halen’s wonderful [sic] album, The Right Stuff, and my second semester of college. It would also prove to be a time of enlightenment for me and computing. On this 30th anniversary of the Apple Macintosh on January 25 and the Superbowl commercial on January 22. I wanted to share my own story of the way the introduction of the Macintosh profoundly changed my path in life.

Perhaps a bit indulgent, bit it seemed worth a little backstory. I think everyone from back then is feeling a bit of nostalgia over the anniversary of the commercial, the product, and what was created.

High School, pre-Macintosh

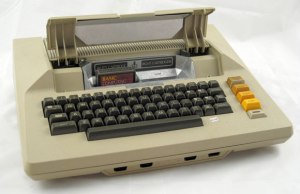

Like many Dungeons and Dragons players my age, my first exposure to post-Pong computing was an Atari 800 that my best friend was lucky enough to have (our high school was not one to have an Apple ][ which hadn’t really made it to suburban Orlando). While my friends were busy listening to the Talking Heads, Police, and B-52s, I was busy teaching myself to program on the Atari. Even though it had the 8K BASIC cartridge it lacked tape storage. Every time I went over to use the computer I had to start over. Thinking about business at an early age (I suppose) I would continue to code and refine what I thought would be a useful program for our family business, the ability to compute sales tax on purchases from different states. Enter the total sale, compute the sales tax for a state by looking up the rate in a table.

My father, an entrepreneur but hardly a technologist, was looking to buy a computer to “automate” our family business. In 1981, he characteristically dove head first into computing and bought an Osborne I. For a significant amount of money ($1,795, or $4,600 today) we owned an 8 bit CPU and two 90K floppy drives and all (five) of the business programs one could ever need.

I started to write a whole business suite for the business (inventory, customers, orders) in BASIC which is what my father had hoped I would conjure up (in between SATs and college prep). Well that was a lot harder than I thought it would be (so were the SATs). Then I discovered dBase II and something called a “database” that made little sense to me in the abstract (and would only come to mean something much later in my education). In a short time I was able to create a character-based system that would be used to run the family business.

To go to college I had a matching Osborne I with a 300b modem so I could do updates and bug fixes (darn that shipping company–they changed the rate on COD shipments right during midterms which I had hard-coded!).

College Fall Semester

I loaded up the Osborne I and my Royal typewriter/daisy wheel/parallel port “letter quality” printer and was off to sunny Ithaca.

Computer savvy Cornell issued us our “BITNET electronic mail accounts”, mine was TGUJ@CORNELLA.EDU. Equal parts friendly, memorable, and useful and no one knew what to do with them. The best part was email ID came printed on a punch card. As a user of an elite Osborne I felt I went back in time when I had to log on to the mainframe from a VT100 terminal. The only time I ever really used TGUJ was to apply for a job with Computer Services.

I got a job working for the computer services group as a Student Terminal Operator (STO). I had two 4 hour shifts. One was in the main computer science major “terminal room” in Upson Hall featuring dozens of VT100 terminals. The other shift was Friday night (yes, you read that correctly) at the advanced “lab” featuring SGI graphics workstations, IBM PC XTs, an Apple Lisa, peripherals like punch card machines, and a 5′ tall high-speed printer. For the latter, I was responsible for changing the ribbon, a task that required me to put on a mask and plastic arm-length gloves.

It turned out that Friday night was all about people coming in to write papers on the few IBM/MS-DOS PCs using WordPerfect. These were among the few PCs available for general purpose use. I spent most of the time dealing with graduate students writing dissertations. My primary job was keeping track of the keyboard templates that were absolutely required to use WordPerfect. This experience would later make me appreciate the Mac that much more.

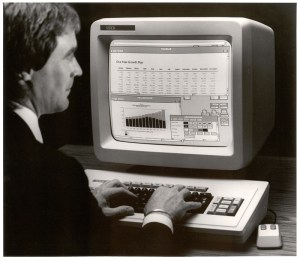

In the computer science department I had a chance to work on a Xerox Star and Alto (see below) along with Sun Workstations, microVAX mini, and so on. The resources available were an incredible blessing to the curious. The computing world was a cacophony of tools and platforms with the vast majority of campus not yet tapping into the power of computing and those that did were using what was most readily accessible. Cornell was awash in the sea of different computing platforms, and to my context that just seemed normal, like there were a lot of different types of cars. This was especially apparent from my vantage point in the computer facilities.

One experience with a new, top-secret, computer was about to change all that.

I ended up getting to use a new computer from an unidentified company. One night after my shift, a fellow STO dragged me back to Upson Hall and took me into a locked room in the basement. There I was able to see and use a new computer. It was a wooden box attached to a wall with an actual chain. It had a mouse, which used on the Xerox and Sun workstations. It had a bitmap screen like a workstation. It had an “interface” like the Xerox. There was a menu bar across the top and a desktop of files and folders. It seemed small and much more quiet than the dorm-refrigerator sized units I was used to hearing.

What was really magical about it was that it had a really easy to use painting program that we all just loved. It had a “word processor”. It was much easier to use than the Xerox which had special keys and a somewhat overloaded desktop metaphor. It crashed a lot even after a short time using it. It also started up pretty quickly. Most everything we did with it felt new and different compared to all the other computers we used.

The end of the semester and exams approached. The few times and couple of hours I had to play with this computer were exciting. In the sea of computing options, it was definitely the most exciting thing I had experienced. Perhaps being chained to the wall added to the excitement, but there was something that really resonated with us. When I try to remember the specifics, I mostly recall an emotional buzz.

My computing world was filled with diversity, and complexity, which left me unprepared for the way the world was going to change in just the next six weeks.

Superbowl

To think about Apple’s commercial, one really has think about the context of the start of the year 1984. The Orwellian dialog was omnipresent. Of course as freshman in college we had just finished our obligatory compare/contrast the dystopian messages in Animal Farm, Brave New World, and 1984 not to mention the Cold War as front and center dialog at every turn. The country emerging from recession gave us all a contrasting optimism.

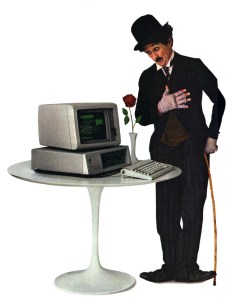

At the same time, IBM was omnipresent. IBM was synonymous with computing. Sure the Charlie Chaplin ads were great, but the image of computing to almost everyone was that of the IBM mainframe (CORNELLA was located out by the Ithaca airport). While IBM was almost literally the pillar of innovation (just a couple of years later, scientists at IBM would spell IBM with Xenon atoms), there was also great deal of distrust given the tenor of the time. The thought of a globally dominant company, a computer company, was uncomfortable to those familiar with fellow Cornellian Kurt Vonnegut’s omnipresent RAMJAC.

Then the Apple commercial ran. It was truly mesmerizing (far more so to me than the Superbowl). It took me about one second to stitch together all that was going on right before my eyes.

Apple was introducing a new computer.

It was going to be a lot different from the IBM PC.

The world was not going to be like 1984.

And most importantly, the computer I had just been playing with weeks earlier was, in fact, the Apple Macintosh.

I was so excited to head back to the terminal rooms and talk about this with my fellow STOs and to use the new Apple Macintosh.

Returning

Upon returning to the terminal room in Upson, Macs had already started to replace VT100s. First just a couple and then over time, terminal access moved to an emulation program on Macs (rumor had it that the Macs were actually cheaper than terminals!).

My Friday night shift was transformed. Several Macs were added to the lab. I had to institute a waiting list. Soon only the stalwarts were using the PCs. I started to see a whole new crowd on those lonely computer nights.

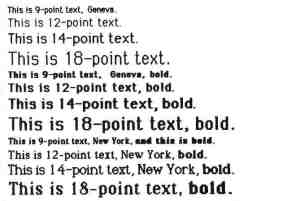

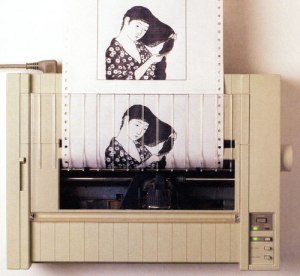

I saw seniors in Arts & Sciences preparing resumes and printing them on the ImageWriter (note, significantly easier to change the ribbon, which I had to do quite often every night). Those in the Greek System came by for help making signs for parties. Students discovered their talent with MacPaint pixel art and fat bits. All over campus signs changed overnight from misaligned stencils to ImageWriter printouts testing the limits of font faces per page.

I have to admit, however, I spent an inordinate amount of time attempting to recover documents that were lost to memory corruption bugs on the original MacWrite. The STOs all developed a great trouble shooting script and signs were posted with all sorts of guesses (no more than 4 fonts per document, keep documents under 5 pages, don’t use too many carriage returns). We anxiously awaited updates and students would often wait in line to update their “MacWrite disks” when word spread of an update (hey, there was no Internet download).

In short order, Macintosh swept across campus. Cornell along with many schools was part of Apple’s genius campaign on campuses. While I still had my Osborne, I was using Macintosh more often than not.

Completing College

The next couple of years saw an explosion of use of Macintosh across campus. The next incoming class saw many students purchasing a Mac at the start of college. Research funds were buying Macs. Everywhere you looked they were popping up on desks. There was even a dedicated store just off campus that sold and serviced Macs. People were changing their office furniture and layout to support using a mouse. Computer labs were being rearranged to support local printers and mice. The campus store started stocking floppy disks, which became a requirement for most every class.

Document creation had moved from typewriters and limited use of WordPerfect to near ubiquitous use of MacWrite practically by final exams that Spring. Later, Microsoft Mac Word, which proved far more robust became the standard.

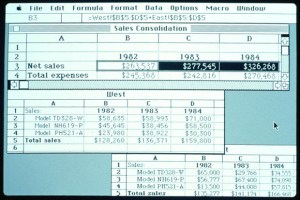

The Hotel School’s business students were using Microsoft Mac Excel almost immediately.

The Chemistry department made a wholesale switch to Macintosh. The software was a huge driver of this. It is hard to explain how difficult it was to prepare a chemistry journal article before Macintosh (the department employed a full time molecular draftsman to prepare manuscripts). The introduction of ChemDraw was a turning point for publishing chemists (half my major was chemistry).

It was in the Chemistry department where I found a home for my fondness of Macintosh and an incredibly supportive faculty (especially Jon Clardy). The research group had a little of everything, including MS-DOS PCs with mice which were quite a novelty. There were also Macs with external hard drives.

I also had access to MacApp and the tools (LightSpeed Pascal) to write my own Mac software. Until then all my programming had been on PCs (and mainframes, and Unix). I had spent two summers as an intern (at Martin Marietta, the same company dBase programmer Wayne Ratliff worked!) hacking around MS-DOS writing utilities to do things that were as easy as drag and drop on a Mac or just worked with MacWrite and Mac Excel. As fun as learning K&R, C, and INT 21h was, the Macintosh was calling.

My first project was porting a giant Fortran program (Molecular Mechanics) to the Mac. Surprisingly it worked (perhaps today, equally surprising was the existence of a Fortran compiler). It cemented the lab’s view that the Macs could also be for work, not just document creation. Next up I just started exploring the visualizations available on the Mac. Programming graphics was all new to me. Programming an object-oriented event loop seemed mysterious and indirect to me compared to INT 21h or stdio.

But within a few hacking sessions (fairly novel to the chemistry department) the whole thing came together. Unlike all of the previous systems I used, the elegance of the Mac was special. I felt like the more I used it the more it all made sense. When I would bury myself in Unix systems programming it seemed more like a series of things, tricks, you needed to know. Macintosh felt like a system. As I learned more I felt like I was able to guess how new things would work. I felt like the bugs in my programs were more my bugs and not things I misunderstood.

The proof of this was that through the Spring semester my senior year I was able to write a program that visualized the periodic table of the elements using dozens of different variables. It was a way to explore periodicity of the elements. I wrote routines for an X-Y plot, bar charts, text tables, and the pièce de résistance was a 2.5-dimensional perspective of the periodic table showing a single property (commonly used to illustrate the periodic nature of electron affinity). I had to ask a lot of friends who were taking computer graphics on SGIs for help! Still, not only had I just been able to program another new OS (by then this was my 5th or 6th) but I was able to program a graphical user interface for the first time.

MacMendeleev was born.

The geek in all of us has that special moment when at once you feel empowered and marvel at a system. That day in the spring of 1987 when I rendered a perspective drawing from my own code on a system that I had seen go from a chained down plywood box to ubiquity across campus was magical. Even my final report for the project was, to me, a work of art.

The geek in all of us has that special moment when at once you feel empowered and marvel at a system.

It wasn’t just the programming that was possible. It wasn’t just the elegance and learnability of the system. It wasn’t even the ubiquity that the Macintosh achieved on campus. It was all of those. Most of all it represented a tool that allowed me to realize some of my own potential. I was awful at Chemistry. Yet with Macintosh I was able to contribute to the department and probably showed a professor or two that in spite of my lack of actual chemistry aptitude I could do something (and dang, my lab reports looked amazing!). I was, arguably, able to learn some chemistry.

I achieved with Macintosh what became one of the most important building blocks in my education.

I’m forever thankful for the empowerment that came from using a “bicycle of the mind”.

I’m forever thankful for the empowerment that came from using a “bicycle of the mind”.

What came next

Graduate school diverged in terms of computing. We used DEC VMS, though SmallTalk was our research platform. So much of the elegance of the Macintosh OS (MacApp and Lisa before that) was much clearer to me as I studied the nuances of object-oriented programming.

I used my Macintosh II to write papers, make diagrams, and remote into the microVAX at my desk. I also used Macintosh to create a resume for Microsoft with a copy of Microsoft Word I won at an ACM conference for my work on MacMendeleev.

I also used Macintosh to create a resume for Microsoft with a copy of Microsoft Word…

When I made it to Microsoft I found a great many shared the same experience. I met folks who worked on Mac Excel and also had Macs in boxes chained to tables. I met folks who wrote some of those Macintosh programs I used in college. So many of the folks in the “Apps” team I was hired into that year grew up on that unique mixture of Mac and Unix (Microsoft used Xenix back then). We all became more than converts to MS-DOS and Windows (3.0 was being developed when I landed at Microsoft).

There’s no doubt our collective experiences contribute to the products we each work on. Wikipedia even documents the influence of MacApp on MFC (my first product contribution), which was by design (and also by design was where not to be influenced). It is wonderful to think that through tools like MFC and Visual Basic along with ubiquitous computing, Windows brought to so many young programmers that same feeling of mastery and empowerment that I felt when I first used Macintosh.

Fast-forwarding, I can’t help but think about today’s college students having grown up hacking the web but recently exposed as programmers to mobile platforms. The web to them is like the Atari was to me—programmable, understandable, and fun. The ability to take your ideas, connect them to the Internet, touch your creation, and make your own experience must feel like building a Macintosh program from scratch felt like to me. The unique combination of mastery of the system, elegance of design, and empowerment is what separates a technology from a movement.

Macintosh certainly changed my path in life…

For me, Macintosh was an early contributor to my learning, skills, and ultimately my self-confidence. Macintosh certainly changed my professional path in life. For sure, 1984 was not at all like 1984 for me.

Yes, of course I’m a PC (and definitely a Surface). Nothing contributed more to my professional life than the PC!

–Steven Sinofsky (@stevesi, stevesi@mac.com)

PS: How far have we come? Check out this Computer Chronicles from 1985 where the new Macintosh is discussed.

If at first you don’t succeed: disrupting incumbents in the enterprise

I was talking with a founder/CEO of an enterprise startup about what it is like to disrupt a sizable incumbent. In the case we were talking about the disrupting technology was losing traction and the incumbent was regaining control of the situation, back off their heels, and generally felt like they had fended off the “attack” on a core business. This causes a lot of consternation at the disrupting startup as deals aren’t won, reviews and analyst reports swing the wrong way, and folks start to question the direction. If there really is a product/market fit, then hold on and persevere because almost always the disruption is still going to happen. Let’s look at why.

I was talking with a founder/CEO of an enterprise startup about what it is like to disrupt a sizable incumbent. In the case we were talking about the disrupting technology was losing traction and the incumbent was regaining control of the situation, back off their heels, and generally felt like they had fended off the “attack” on a core business. This causes a lot of consternation at the disrupting startup as deals aren’t won, reviews and analyst reports swing the wrong way, and folks start to question the direction. If there really is a product/market fit, then hold on and persevere because almost always the disruption is still going to happen. Let’s look at why.

Incumbent Reacting

The most important thing to realize about a large successful company reacting to a disruptive market entry is that every element of the company just wants to return to “normal” as quickly as possible. It is that simple.

Every action about being disrupted is dictated by a desire to avoid changing things and to maintain the status quo.

If the disruption is a product feature, the motion is figuring out how to tell customers the feature isn’t that important (best case) or how to quickly add something along the lines of the feature and move on (worst case). If the disruption is a pricing change then every effort is about how to “manage customers” without actually changing the price. If the disruption is a new and seemingly important adjacent product, then the actions focus on how to point out that such a product isn’t really necessary. Across the spectrum of potential activities, it is why the early competitive responses are often dismissive or outwardly ignore the challenger. Aside from the normal desire to avoid validating a new market entry by commenting, it takes a lot of time for a large enterprise to go through the work to formulate a response and gain consensus. Therefore an articulate way of changing very little has a lot of appeal.

Status quo is the ultimate goal of the incumbent.

Once a disruptive product gains enough traction that a more robust response is required, the course of action is almost always one that is designed to reduce changes to plans, minimize effort overall, and to do just enough to “tie”. Why is that? Because in a big company “versus” a small company, enterprise customers tend to see “a tie as a win to the incumbent”. Customers have similar views about having their infrastructure disrupted and wish to minimize change, so goals are aligned. The idea of being able to check off that a given scenario is handled by what you already own makes things much easier.

Keep in mind that in any organization, large or small, everyone is at or beyond capacity. There’s no bench, no free cycles. So any change in immediate work necessarily means something isn’t going to get done. In a large organization these challenges are multiplied by scale. People worry about their performance reviews; managers worry about the commitments to other groups; sales people worry about quarterly quotas. All of these worries are extremely difficult to mitigate because they cross layers of managers and functions.

As much as a large team or leader would like to “focus” or “wave a wand” to get folks to see the importance of a crisis, the reality of doing so is itself a massive change effort that takes a lot of time.

This means that the actions taken often follow a known pattern:

- Campaign. The first thing that takes place is a campaign of words and positioning. The checklist of features, the benefits of the existing product, the breadth of features of the incumbent compared to the new product, and so on. If the new product is cheaper, then the focus turns to value. Almost always the campaign emphasizes the depth, breadth, reliability, and comfort of the incumbent’s offer. A campaign might also be quite negative and focus on a fear, compatibility with existing infrastructure, or conventional wisdom weakness of a disruptor, or the might introduce a pretty big leap of repositioning of the incumbent product. A good example of this is how on-premises server products have competed with SaaS by highlighting the lack of flexibility or potential security issues around the cloud. This approach is quick to wind up and easy to wind down. Once it starts to work you roll it out all over the world and execute. Once the deals are won back then the small tiger team that created the campaign goes back to articulating the product as originally intended, aka normal.

- Partnership. Quite often there can be a competitive response of best practices or a third-party tool/add-on that appears to provide some similar functionality. The basic idea is to use someone else to offer the benefit articulated by a disruptive product. Early in the SaaS competition, the on-premises companies were somewhat quick to partner with “hosting” companies who would simply build out a dedicated rack of servers and run the traditional software “as a service”. This repotting plants approach to SaaS has the benefit that once the immediate crisis is mitigated, either the need to actually offer and support the partnership ends or the company just becomes committed to this new sales channel for existing products. Again, everything else continues as it was.

- Special effort. Every once in a while the pressure is so great internally to compete that the engineering team signs up for a “one off” product change or special feature. Because the engineering team was already booked, a special effort is often something carefully negotiated and minimized in scope and effort. Engineering minimizes it internally to avoid messing up dependencies and other features. Sales will be specific in what they expect the result to do because while the commitment is being made they will likely begin to articulate this to red-hot customer situations. At the extreme, it is not uncommon for the engineering team to suggest to the sales organization that a consultant or third-party can use some form of extensibility in the product to implement something that looks like the missing work. The implications of doing enterprise work in a way that minimizes impact is that, well, the impact is minimized. Without the proper architecture or an implementation at the right level in the stack, the effort ultimately looks incomplete or like a one-off. Almost all the on-premise products attempting to morph into cloud products exhibit this in the form of features that used to be there simply not being available in the “SaaS version”. With enough wins, it is almost likely that the special effort feature doesn’t ever get used. Again, the customer is just as likely to be happy with the status quo.

All of these typical responses have the attribute that they can be ignored by the vast majority of resources on a business. Almost no one has to change what they are doing while the business is responding to a disruptive force. Large incumbents love when they can fend off competitors with minimal change.

Large incumbents love when they can fend off competitors with minimal change.

Once the initial wave of competitive wins settles in and the disruptive products lose, there is much rejoicing. The teams just get back to what they were doing and declare victory. Since most of the team didn’t change anything, folks just assume that this was just another competitor with inferior products, technology, approaches that their superior product fended off. Existing customers are happy. All is good.

Or is it?

Disruptor Persevering

This is exactly where the biggest opportunity exists for a disruptive market entry. The level of complacency that settles into an incumbent after the first round of victories is astounding. There’s essentially a reinforcing feedback loop because there was little or no dip in revenue (in fact if revenue was growing before then it still is), product usage is still there, customers go back to asking for features the same as they were before, sales people are making quota, and so on. Things went back to normal for the incumbent.

In fact, just about every disruption happens this way–the first round or first approaches don’t quite take hold.

Why is this?

- Product readiness can improve. Obviously the most common is that the disruptive product simply isn’t ready. The feature set, scale, enterprise controls, or other attributes are deficient. A well-run new product will have done extensive early customer work knowing what is missing and will balance launching with these deficiencies and with the ability to continue to develop the product. In a startup environment, a single company rarely gets a second shot with customers so calibrating readiness is critical. Relative to the broader category of disruption, the harsh reality is that if the disruptor’s idea or approach is the right one but the entry into the market was premature, the learning will apply to the next entry. That’s why the opportunity for disruption is still there. It is why time to market is not always the advantage and being able to apply learning from failures (your own or another entry) can be so valuable.

- Missing ingredient gets added. Often a disruptive product makes a forward-looking bet on some level of enterprise infrastructure or capability as a requirement for the new product to take hold. The incumbent latches on to this missing ingredient and uses it to create an overall state of lack of readiness. If there’s one thing that disruptors know, it is not to bet against Moore’s law. If your product takes more compute, more storage, or more bandwidth, these are most definitely short-term issues. Obviously there’s no room for sloppy work, but by and large time is on your side. So much of the disruption around mobile computing was slowed down by the enterprise issues around managing budgets and allocation of “mobile phones”. Companies did not see it as likely that even better phones would become essential for life outside of work and overwhelm the managed phone process. Similarly, the lack of high-speed mobile networks was seen as a barrier, but all the while the telcos are spending billions to build them out.

- Conventional wisdom will change. One of the most fragile elements of change are the mindsets of those that need to change. This is even more true in enterprise computing. In a world where the average tenure of a CIO is constantly under pressure, where budgets are always viewed with skepticism, and where the immediate needs far exceed resources and time, making the wrong choice can be very costly. Thus the conventional wisdom plays an important part in the timeline for a disruption taking hold. From the PC to the GUI to client/server, to the web, to the cloud, to acceptance of open source each of these went through a period where conventional wisdom was that these were inappropriate for the enterprise. Then one day we all wake up to a world where the approach is required for the enterprise. The new products that are forward-looking and weather the negatives wishing to maintain the status quo get richly rewarded when the conventional wisdom changes.

- Legacy products can’t change. Ultimately the best reason to persevere is because the technology products you’re disrupting simply aren’t going to be suited to the new world (new approach, new scenarios, new technologies). When you re-imagine how something should be, you have an inherent advantage. The very foundation of technology disruption continues to point out that incumbents with the most to lose have the biggest challenges leading through generational changes. Many say the enterprise software world, broadly speaking, is testing these challenges today.

All of these are why disruption has the characteristic of seeming to take a much longer time to take hold than expected, but when it does take hold it happens very rapidly. One day a product is ready for primetime. One day a missing ingredient is ubiquitous. One day conventional wisdom just changes. And legacy products really struggle to change enough (sometimes in business or sometimes in technology) to be “all in” players in the new world.

Of course all this hinges on an idea plus execution of a disruptive idea. All the academic theory and role-playing in the world cannot offer wisdom on knowing if you’re on to something. That’s where the team and entrepreneur’s intuition, perseverance, and adaptability to new data are the most valuable assets.

The opportunity and ability to disrupt the enterprise takes patience and more often than not several attempts, by one or more players learning and adjusting the overall approach. The intrinsic strengths of the incumbent means that new products can usually be defended against for a short time. At the same time the organization and operation of a large and successful company also means that there is near certainty that a subsequent wave of disruption will be stronger, better, and more likely to take hold simply because of the desire for the incumbent to get back to “normal”.

–Steven Sinofsky (@stevesi)

A product management view of CES 2014

I love the Consumer Electronics Show. Maybe I’m numb from decades of attending it. Maybe I’m just too much of a fan of watching stuff get made. Maybe I just like long lines and the potential for airborne illness. Really what I love is the technology industry and that every year we get together and demo new products, share works in progress, and take chances on offering products people don’t yet (or ever) know they want. CES 2014 was an exceptionally unique year and one that I think will be remembered as the start of a new era, much how the 1970 show changed TV with the introduction of the VCR or the 1981 show changed music with the CD player.

I love the Consumer Electronics Show. Maybe I’m numb from decades of attending it. Maybe I’m just too much of a fan of watching stuff get made. Maybe I just like long lines and the potential for airborne illness. Really what I love is the technology industry and that every year we get together and demo new products, share works in progress, and take chances on offering products people don’t yet (or ever) know they want. CES 2014 was an exceptionally unique year and one that I think will be remembered as the start of a new era, much how the 1970 show changed TV with the introduction of the VCR or the 1981 show changed music with the CD player.

CES 2014 was an exceptionally unique year and one that I think will be remembered as the start of a new era.

But wait, you ask “What product was launched at CES 2014?” The answer is “None”. Instead, this is a year in which every product is about software, and every product assumed that the computer involved would be based on modern mobile platforms, and most everything connected to a cloud service. As an industry we’re not there yet, as we will talk about below, some offerings still cling to previous models of accessing computing and we’re likely to see much changing of the guard as breakthrough products emerge.

The ubiquity of the modern mobile platform, smartphones and tablets, might seem obvious to all of us in computing proper, but it took the better part of a decade for it to go from a section of the show to a big presence to woven into the fabric of every exhibitor. Likewise, software has gone from “content” to “console games” to “pc applications that get thrown in with a device” to the raison d’être or differentiation of consumer electronics.

So put aside the lines, the endless sameness of non-differentiated products, the puzzling keynotes, or even the absence of Apple and Google, and consider the over 3200 companies of all sizes showing off products of all kinds. For me, I think back to when I was a kid and the excitement around what was next came at the yearly Auto Show or reading about the historical World’s Fair Expos. It is hard to avoid concluding that CES is our era’s expression of the future—transportation, healthcare, communication, entertainment, and more are represented by the innovation on display at CES.

It is hard to avoid concluding that CES is our era’s expression of the future—transportation, healthcare, communication, entertainment, and more are represented by the innovation on display at CES.

Me, I’m just excited to get to go to the show and systematically walk up and down every aisle exploring what is there to see. My one set of eyes and one post can’t compete with the likes of the professional tech press that push out hundreds of posts during the week or with the amazingly thorough coverage of “best of” done by many.

Instead, I offer these observations or themes from a product development perspective—what would I be looking at as a product manager or engineer. As I’ve said in this blog many times, learning comes from observing and sharing. Product plans come from many points of view and sources coming together in the context of a company. I cover a lot, but there is more. It was a great show for learning and thinking about the next phase of our industry.

This report looks at themes covering embedded smarts, healthcare devices, communication wearables, screens (4K, curved, skinny), less futzing, and overall trends up/down.

First, a bit of humility

One thing required when looking at new products and technologies is humility. Even though many would like to differ, CES is not a shopping mall where you go to find the new big thing to buy or use right away. This is counter-intuitive because a lot of the products at CES are new and for sale. But in practice, they have not been used and many times not even released to reviewers yet. So you want to step back as you read about the products and not look through the lens of “would I buy and use this today” and instead think about the context overall. As part of that I like to remind myself of a few things about what we see:

- Companies aren’t dumb. A lot of times when a product is first seen something jumps out at you as totally wrong. Keep in mind many of the products are not about the use cases for today, but for use cases yet to be seen. The most classic example is the Walkman— a “tape recorder” that didn’t record. Or more recently, a digital camera that is bigger, heavier, costlier, and worse than a film camera. Sometimes the new use cases aren’t even obvious to the companies yet, and this is even more true today as many “hardware” companies are moving forward rapidly with hardware or the supply chain is making available new components because it can, neither really having software that can implement new use cases.

- Limitations seen in less than one minute are known by the product people. Every product has issues, limitation, constraints. Walking up to a brand new product and thinking you’re the first person to notice such is usually a mistake. While the person at the booth might know the FAQ, it is a good idea to assume the product folks back at HQ actually know the limitations. I can’t count how many times people commented on the battery life of one of the wearables with screens—as though the people developing them would not like to have a month of battery life or were not aware of the trade-off between weight and battery life.

- Iteration is baked into the product you are seeing. Even though the product is for sale, it might not be done yet. It will get smaller, faster, cheaper, power efficient, lighter, and more feature rich. It will do so quickly. Many of those plans are in place. Because so much of the hardware is now subject to Moore’s Law, it is already happening and you can just wait—the price of 4K displays will drop rapidly and because of 1080P volume the price is already spectacular compared to what we’ve come to expect based on previous generations. For software, we all know updates and features are part of the plan. There’s no guarantee things will go in the “right” direction for every product but iteration will happen. Because there are many players, keep in mind that iteration by one player becomes learning for another player so there is ample opportunity for changes in leadership. We all know in technology, first mover advantage is not necessarily an advantage. Multi-party, iteration is the reason.

- Core competency matters. With so many devices doing so many things and so many products incorporating features from other products for differentiation, it is important to focus on the core competency of a product. There’s a good chance a product will try to do too much or for that matter all the products will try to differentiate themselves based on some peripheral features. Don’t lose sight that TVs should have a good picture, fitness bands should measure your fitness well, scales should be fast and easy to read, speakers should sound good and so on.

- Everything has depth and experts. Every year I get surprised by some product that I never thought of and think how amazing that idea is, and then I see 3 more of them on the show floor. It is easy to forget that inside the CE industry there are many industries. Within those industries are people who spend their careers mastering something that, to the uninitiated, might seem narrow. I saw a modern blood sugar monitor (see below) this year that was totally unique. Then I saw two more. These experts are all feeding off many of the same inputs and so one should expect some degree of convergent innovation. Said another way, in the context of a broad show like CES, something that I think is really cool might not actually be all that innovative to those in the field with some domain knowledge.

Themes

Let’s look at some themes and within them put on our product manager hats and see how what we observed might influence our own choices in products design. I’m going to take the observations from the show floor and project forward a bit as that’s what product management needs to do with the data when there are technology bets to be made, products to design, and specs to write.

Embedded smarts

Intel kicked off the show with a keynote declaring that all devices need to be smart. Walking around the show floor showed that this advice has already been taken to heart. While smart TVs are the most obviously visible (and also a holdover from the past two or so years), we also saw smart cars, smart healthcare devices, smart fitness monitors, smart watches, smart home appliances, smart projectors, and more. Smart was everywhere. Should it be?

Smart can mean anything from a touch-based user interface replacing the existing mechanical UI to taking a formerly mechanical device and embedding an entire OS with app ecosystem into the device.

Moore’s Law is an important contributor to this trend. Previous views of smart devices would have meant connecting the hardware device to a PC, with all of the costs, size, power that this entails. Home automation that used to take a PC now just connects devices with Wi-Fi to a cloud service, for example. A home blood pressure monitor would have stored some number of readings until you connected it with a serial cable to a PC and now it just sends those over Wi-Fi to a cloud service. TVs would have been connected to a PC that presented a full PC experience through an alternate user interface that today can offer this same type of functionality through an entirely embedded solution. Now it is both feasible and economic to include an ARM-based computing platform and either a Linux or Android OS driving the “smarts”.

But is this always right? The product manager view might be that it is time to look at use cases and scenarios and step back. While the hardware side is possible, the software might not be delivering the right experience. The truth is, some devices should be dumb. And that’s ok. The internet of things does not need to recreate the challenges of the internet of PCs. A single general purpose approach used everywhere might not be the best approach compared to tailored devices working with a very rich mobile device and cloud services.

The truth is, some devices should be dumb. And that’s ok.

One reason for this is that there can only be so many app ecosystems. It simply won’t be possible for apps to be delivered reliably and in a feature complete manner across all of the various smart devices. While today it might be possible for a streaming music service to be omnipresent on every possible smart device from a watch to a car to a TV to a refrigerator to a treadmill (and a phone and a tablet), down the road the user experience for that streaming app will have become rich enough that the primary use case will drive the expected experience which won’t be duplicated across devices, whether that is because the devices vary in capabilities, screen sizes, or just human interaction or just because there are too many different platforms.

Two examples help to reinforce this product challenge.

- Screens / TV. We all want lots of stuff on our big screens. We want streaming video, live broadcast television, music (maybe), and perhaps some web services like messaging. But these are all sophisticated experiences (finding the video, dealing with TV signals/guides/DVR, managing playlists, different apps), and so it means they likely demand (or will demand) a rich interaction model connected to services. Good news! We already have this interaction model on our modern mobile tablets and phones. Why try to duplicate this with the added complexity and variety of TVs? Rather a device like Chromecast or Apple TV shows how you can use the TV simply as a “dumb screen” which becomes far more manageable, the UI is far better, and is a much better overall experience. These solutions, where the screen is dumb and the mobile device serves as the gateway to the dumb screen seem to put the code in the right place and reduce complexity and increase simplicity for the use case. It is worth asking if this Twitter client on a TV will ever match what you can do on your mobile device in your hand while watching the show? That’s not to say there won’t be other use cases integrating apps into TV, but just showing subsets of the mobile apps side by side doesn’t seem right.

- Autos. From Audi to Volvo we saw smarts added to cars. This was added in the form of a screen, a telemetry platform, and apps. What is different about this compared to TVs is that we don’t want cars to be dumb. We want cars to be smart about being cars (safety, maintenance, better driving and accident avoidance). Like TVs, however, it isn’t clear that we want to put the equivalent of a unique mobile platform in every car brand. Is there any chance the mapping app in a car will be on par with the mapping app in my mobile device? Wouldn’t I rather have the same ability to send my mobile screen to the car screen that I get with Chromecast or Apple TV? Perhaps having a protocol that supports touch in that scenario is very helpful too. In the meantime the smarts of the car can focus on the things the car needs to do, and perhaps even recognize the best way to have a user experience and manage those would be with an app and cloud service? Ultimately, the way cars are made means that the technology choices are out of date by the time the car makes it to market and if you own the car for 5 years then those technology choices are really dated and perhaps the overall resale value of the car declines.

Will this UX really be right today or in 8 years?

The fact that all the screens and cars are making bets on technologies that are just capable of being used helps us all—this is not the time to be cynical but the time to learn. These products are not done yet and we can’t highlight the greatness of the Lean Startup and MVP and then be critical of bringing to market products that might not quite be done—that’s where reviews, experts, and frankly store return policies can help. As a product manager you want to ask yourself about the trajectory and likelihood of success of an approach down the road when the work all comes together. These new products show exciting scenarios but maybe there are better ways to implement them.

Healthcare devices

The advances in sensors have been breathtaking thanks to technologies like MEMS and others. Combining those with the ability to embed and whole OS and connectivity to cloud services in what used to be basic diagnostic equipment is a revolution in healthcare. Here too we saw many new and breakthrough products. As a telemetry nut, obsessive compulsive, and geek these are some of the most exciting products ever. One thing that made this CES seem so new and fresh is that this feels like a renaissance in consumer electronics. Devices you buy at reasonable price points, solve specific problems like an appliance, and just work for a scenario. In most ways, these new devices are starting to deliver now.

Basic body telemetry like weight, blood pressure, composition and more can now be easily measured, tracked over time, and even shared easily with care givers or compared with a circle of friends. Stepping on a scale every morning is quietly making a bar chart, setting alerts, and trending your data. And even better, such devices are learning from past designs and becoming easier to setup and use. No longer do you need a PC, EXE, and USB cable. Instead the device is paired over Bluetooth with a dedicated app and you’re up and running with a great UI in no time. Basic scenarios like maintaining compliance with medication are made easier by smart pill boxes that alert you wirelessly on your mobile device to take medicine. Overkill? Perhaps, but compliance rates are still not where they need to be. And combine this with easy measurement of blood pressure and you can see how putting smart in the right place, cloud services and mobile apps to make things accessible can be such a huge advance.

Three healthcare products that demonstrate this include:

- Head injury. Much has been written about the rise in head injury in sports and long term risk associated with cumulative concussion, particularly football. Reebok with the Checklight is one of many companies with a product designed to measure cumulative head impact using accelerometers. The packaging is very user friendly as you can see (and it won a best of CES award). The basics of the device are cool—a red light goes off when a certain level of cumulative concussion risk has been reached. Other variants of similar devices have different form factors (helmet integrated, mouth guard) and can even report real time to a mobile app. The telemetry, use case, and execution are all coming together at CES 2014.

- UV exposure. The JUNE UV detection bracelet by netamo simply measures cumulative sun exposure and integrates with a mobile app, again with a simple UI on the device and a data connection to a mobile app. There’s a lot to like about this for folks who work or play outdoors and want to mitigate the risk of skin disease or damage. The app/service provides advice and a suggested “routine” for your skin based on data.

- Blood glucose. Those that have been touched by diabetes (perhaps one of the more insidious diseases in the developing world, costing the US an estimated $245B a year in healthcare and related costs) know the complexity and challenges of testing and managing glucose levels. The YoFi Meter, http://www.yofimeter.com/, is a very smart device (see the above discussion). It combines a glucose test strip dispenser/reader, a lancet dispenser, along with a simplified tracking interface on a touch screen and an integrated 3G connection to a cloud data service. This is a device that takes compliance to a new level. At first I might have thought this device is too smart, and then after talking to the designer I learned of many use cases where a companion mobile phone isn’t available or possible (for example, students must be tested by the nurse who doesn’t have time to call up parents with real time data and a phone might not be available in school).

Each of these three devices shows how telemetry and mobile apps/cloud services can dramatically change the basics of healthcare for a scenario.

There are challenges we will all need to deal with however. These challenges are not new to those who already work with data. Data does not always lead to actionable next steps and sometimes more data leads to more ambiguity. These three devices show how the reality is that science is not yet caught up to being able to present us with all this data.

In the case of concussion and head injury, right now the data is unclear on how much cumulative impact over what period of time is “safe”. So while it can be measured, exactly when and how to act is not clear, particularly for children. It is easy to see how the debate will quickly move to one of acceptable levels. So more studies over a longer period of time will be needed which for this type of measurement will take decades given that the measurement is just now available. Science is hard. Glucose measurement is the other end of the spectrum. For diabetics the data and management is well understood, but compliance is challenging or at least not super convenient. The advances are amazing and ready now! Sun exposure is one that becomes interesting only because the data basically says to minimize exposure as much as possible—in other words there’s not really an acceptable level of UV light (i.e. SPF 40, see http://www.aad.org/media-resources/stats-and-facts/prevention-and-care/sunscreens).

Together these show the opportunities and challenges in the healthcare telemetry space. In any product design, the ability to measure something and present the measurement to a customer is not the same as being able to provide reliable and actionable information. It is critical in the design of a product to be clear on what to do when the product tells you something, lest the dreaded “Check Engine’ syndrome.

One might even offer the world’s first connected toothbrush:

Wearable communication

While many healthcare devices are wearable, the broader category itself exploded this year as has been well documented…everywhere. When it comes to sophisticated wearable communication devices, this is a year of learning products. Most are not ready for primetime or broad usage, though many will find niches with early adopters or enthusiasts.

This shouldn’t be news to anyone. Consider as an example post-VHS digital formats for movies forays into optical media (LaserDisc anyone), the path from first products to broadly used products is often one with many twists and turns in basic technology and scenarios. In addition that path from the first component sized DVD player to the 6″ round portable DVD player or integrated flat screen DVD player took some time. Innovation does not happen all at once, even though we often remember it as punctuated moments in time.

There’s no need to document the dozens of communication wearables on display. Most shared the same basic characteristics, with Pebble being the established player that has already earned an enthusiastic base of early adopters. These pair with a mobile device, share notifications, and permit some level of interactivity and apps/ecosystem. Some do less and trade off towards a longer battery life by doing less. Others try to subsume the mobile device entirely and act as a phone (see below).

The primary “cause” of this is that the ability to miniaturize the hardware platform and squeeze a full software platform on the device has surpassed the ability to build a software experience and use case. These devices, by and large, are currently in the “because we can” phase of innovation. That’s not bad and in fact when software meets hardware it is often a necessary ordering.

The primary challenge, at least from my perspective, is that no one has arrived at a new use case. We’re simply looking to move some use cases of the mobile device to a wrist based device. But the device on the wrist is “less of everything”. Taking a disruption point of view, this isn’t disruptive yet. As often discussed, the first PC-derived tablets were more PCs without keyboards than they were a new set of use cases (pen based drawing/notetaking notwithstanding). It wasn’t until the iPad presented a new set of mobile scenarios and capabilities and the hardware was better able to meet the scenarios that a device without a keyboard was able to define a new use case.

Absent a use case, the dialog around wearables will just bounce around the constraints of screen size and battery life. You can only do so much with a tiny screen and a wrist sized device can only operate a screen for so long. While one likes to be notified with a UX based on a glance, it turns out this is pretty much what mobile phone designers work to do all the time and with a lot more screen real estate and elaborate UX. On those platforms the debate is an endless one around how much can you do to a notification and what are the verbs that act on it. Is a new text just read, read and reply with a canned set of replies (and can/how might those be customized), or full messaging capabilities? Do those choices extend to custom messaging apps like WhatsApp or Skype? Who will write those apps? When those apps have new features do they carry over to the wrist?

Here is one example of a fitness watch that is also full smartphone on a wrist, including a pull out Bluetooth headset.

This is a complex set of questions. From a product manager perspective, they all boil down to defining use cases and scenarios for why a device should exist. Is it a companion? Is it a replacement? What does it do uniquely such that I’d be willing to forgo other functions I already have? Disruption theory says that it is totally ok for a new product to do less, so long as it is so good at something that people want more as that’s the whole point of being disruptive.

It is still early. It is too early to judge these devices as what is possible and for most of us too early to be adopting these devices. They are the stuff of Star Trek, which by that theory of innovation only means it is a matter of time.

Screens: 4K, curved, and skinny

If you’ve seen just one article on CES then it is certain you know that new TVs on display were both 4K and curved. Cutting to the chase, if you buy a TV in 2015 odds are it will be 4K. The rapid march to 4K is more massive than anything we’ve seen in screens. Moore’s Law is our friend here and at some point the entire supply chain will just convert to the mechanics of making 4K and it becomes essentially non-economic to maintain the old processes and supply chain. We’ve seen this with memory, storage, processors, and screens. Silicon based innovation lends itself to rapid and whole movement of products. That’s good for all of us.

Cutting to the chase, if you buy a TV in 2015 odds are it will be 4K.

For screens, 4K has two unique elements:

- Extremely rapid cost reduction. Competition is fierce and the economics of the processes will likely drive 4K screens to “acceptable” consumer prices much more quickly than the move to flat screen or 1080P. During the show Dell announced a 4K monitor for $699. My early adopter 15″ VGA LCD costs $1999 (and weighed more than the Dell will). Yay for consumers!

- Content will appear. While we can all bemoan the hype and failure cycle of 3D at home, which included a lack of content, there were already significant content deals for 4K, notably Netflix. While you need 15MB bandwidth for 4K the content will be there. Rest assured, the rest of the content industry heard this and so I suspect we will see brilliant 4K content of some form very rapidly. Again, yay for consumers!!

If you have any doubts, once you see a 4K screen you will want one. Put aside all the arguments about physics, optics, and more, it just feels right. In practice, what you really want are high gamut and 60fps, so let’s hope these attributes and benefits become clear to consumers. Again, this shows the value of reviews, community, and expertise in the adoption of CE.

Curved screens were somewhat of a surprise to many attendees I believe. In booth after booth people had somewhat puzzled looks at them and there seemed to be a broad effort to quiz the booth staff with “so what good is it”. Most of the time we all got the general answers about immersive experience or less reflection. Each of these to some degree are true (especially reflectivity in many situations).

Again, as product managers we see a hardware technology appear because it can but the use case hasn’t yet been determined. Like the first color computer screens that many argued against claiming software was inherently black and white, curved screens are about new use cases not just curving a football game. One view around CES and you can easily see scenarios such as signage that become incredibly cool. Today signs that are interactive are much cooler than static signs (or menus and more). Signs that need to be on curved surfaces are static and boring. Maybe curved displays will be a niche at home and find themselves useful only for commercial signs. I’m going to bet on the creativity of content and product people to develop new use cases and before we know it curved screens will be ubiquitous as “flat screens”.

Finally, this year saw a great many more wide-aspect ratio screens at 21:9. For the most part, the mass market of screens are made in a small set of aspect ratios depending on mass adoption. Like film was historically, there are both benefits to this along with those that want to experiment with alternate aspect ratios. The iOS tablet world is 4:3 and the Windows/Android/HD world is 16:9. The ultra-wide 21:9 seems rather appealing for a number of use cases, including side by side and multiple inputs. If you combine the ultra-wide screen, more pixels, and curved display you recreate a developer workstation or Bloomberg terminal but with a single screen which can mean less space, easier ergonomics, and perhaps less power. Again, it seems like the use cases are going to quickly follow the technical ability to make the screen.

The product manager view of screens is to consider what you app or content can do when being projected on or making content for these new capabilities. As we saw with Retina pixel density, these changes can happen quickly and getting left behind is not always a good spot to be.

Less futzing

The evolution of most CE devices is often to more features and customization, and over time this can be viewed negatively. Certainly at some point this complexity makes products unappealing for many. The industry has a great many enthusiasts who love to customize and tweak. Analogous to the auto shows, some people used to love to look under the hood and adjust the engine.

Back in the heyday of Auto Shows (they are still huge, but CES and tech have eclipsed those shows in media coverage in my biased view), the talk was about components of cars. This dialog was broad and understood. Average consumers knew about horsepower, disc brakes, electronic fuel injection. Today cars are about design, convenience, and use-centric concepts like capacity and MPG. CES, this year in particular, has transitioned to talking and showing more about use cases and less about how products are built.

In almost all devices you have to look hard to find gigahertz or megabytes. You see tasks or uses much more up front. This isn’t always the case and often the first questions are about specs. Still, I would say a lot of “progress”.

Some examples of this jumped out at me, particularly in the gaming world. The gaming world has traditionally been split between consoles representing the true CE experience and the gaming PC which defined the ultimate enthusiast experience when it came to moding your gaming PC. For gamers or those that want to just play games this is a banner time with an explosion in gaming options. Many believe the usage in phones and tablets will dominate with casual games available in app stores. The new consoles from Sony and Microsoft promise to bring gaming to new technical levels with their advanced PC componentry in a true CE package. Finally, at CES we saw the SteamOS powered devices (PCs) and an example of a more state of the art or “modern” PC.

Steam Machine. SteamOS promises to bring the simplicity of consoles with the power of PC gaming. Some critics are saying it brings neither and is in-between. But the popularity of the Steam platform is significant with millions of intensely active members. The product manager question is whether Steam disrupts PC (or console) gaming or simply extends the life of a gaming platform that while popular is being squeezed between consoles and mobile devices. Is the SteamOS powered device re-imagination of PC gaming or an appealing convergence of the PC with consoles (see https://blog.learningbyshipping.com/2014/01/07/the-four-stages-of-disruption/)?

A Steam Machine is an Intel-based device meeting a set of baseline specs, combined with the Steam Controller and SteamOS. The debate among gamers is about the specs and capabilities of the underlying hardware along with the lack of ability to mod the devices. The Steam Machines themselves represent a broad range of “sealed case” form factors, most of which existed as Windows game PCs in various forms.

Razer Project Christine. Razer introduced Christine, which is a highly stylized modular PC. While the idea behind a modular from factor has been tried several times before, the combination of hardware interop, industrial design, and openness to accessorization (my own word) are at a unique point in time. Razer has a very active customer based that thrives the combination of gaming and accessories for gaming. It might just be that this hassle-free notion of moding a gaming PC will appeal to a broad set of PC gaming customers. In many ways this is an attempt to disrupt the PC gamer, while maintaining a commitment to customization. Project Christine beat out Steam Powered for CES Best of Show in the category.

Reduced futzing is really enabled across a broad range of CE devices because of mobile apps, WiFi/Bluetooth connectivity, and cloud services. What used to be elaborate setup and configuration is now enabled via simple apps that connect to devices over wireless protocols. The rich UX afforded by devices replaces single line LED displays or embedded web server experiences. The ability to save/restore data and settings in the cloud replaces sharing via dedicated (and awkward) subset experiences for social networks. From WiFi access points to scales to cameras, we will spend (and tolerate) less time futzing and more time using CE devices.

From a product manager perspective what excites me about these two innovations and the broader theme is the move “up the stack”. Our computing industry has broadly moved to modern platforms for both hardware and software and seeing gaming move in this direction is critical to the health of this style of rich interactive gaming. It is also a natural maturing of a technology area and to resist the change essentially guarantees disruption. The market for people willing to devote time to futzing is shrinking, no matter how much we (having built more PCs than I can count) enjoyed it. There are simply too many options for how to spend more time gaming and less time futzing. Just like people want to use cars to get around, not stare under the hood and fix them before going somewhere, the move up the stack is relentless for most every consumer.

Trending up and down

To wrap up a quick look at the year over year view of CES and what is on the move taking up more floor space and mind share and what is taking less beyond the items mentioned above.

Trending Up

Android. There was a lot more Android this year than last year. Android of course is particularly popular among wearables and TVs where there is no third party option to use iOS. The inexpensive Android tablets we all heard about from the holidays were on display where you could see the dozens of OEMs packaging every conceivable screen size and spec into tablets. One note is that there was a complete absence of 4:3 Android devices, which I find interesting given the competitive nature of things. What this feels like is a reaction to avoid being like Apple, when in practice it might be that for some device sizes the squarer aspect ratio might be more convenient.

Chromebooks. Building off what we might have read as momentum in the US over the holidays was a broader presence of Chromebooks. This year saw an all-in-one along with several lighter and thinner (and still inexpensive) clamshell formats.

Phablets. It was interesting to see the number of show attendees using their really big phones (or small tablets). I would do a quick badge check and noted that more often than not the phablet user was not an employee of Samsung or LG, but just a user. I think this is a trend worth watching. If you have only one device the tradeoff towards a bigger screen becomes interesting.